SADAR+VUGA

An interview with Bostjan Vuga.

Paolo Emilio Belisario: Competitions. Your office opens in 1996 after winning 2 competitions: the Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the extension of the National Gallery in Ljubljana. How important is to get in the game through architectural competitions? And how much weight has the final outcome? Is a victory more useful to designers to have safety and confirmations on their work or is more useful to communicate a positive image of the office to others?

Bostjan Vuga: First of all I would like to thank CityVision magazine for inviting me to be part of the jury in the last competition. It was an hard work to check concepts behind almost 200 proposals but it is a very good initiative, very stimulus to many architects, and also stimulus for me as well.

Competitions are exercises. They are always important tests for offices, or individual architects, for testing design, ideas and techniques of representation. Certain things can be developed just through a competition, so if you put time, energy and effort in to a competition, soon or later it will pay back, like keeping studying through the competition.

Of course it’s not just an academicals exercise. You have to think that you will win and that your building will be built. There is a strong link between testing and building, experimentation and realization. A competition is the right media: because you are independent and just follow the brief of the competition. The client is still an abstract figure. Architects or students who don’t work on competition have a different pace of working that also influences how their building will look like. There is a strong connection between how you organize a competition, how your office is organized and how your building will look like. In our office organizing projects is still based on team work, brainstorming, sitting down together, discussing. This is also represented in our buildings, and this is also the way we avoid stylistic orientation.

This was also our starting point 15 year ago. A competition is also a vehicle for the office to start, because you win the competition and you got financial recourses to open the office.

Then, we won other two competitions: one for the Sport Hall and one for the Fountain, but that’s it. For 8-10 years we didn’t win anything. We hit the reality, not being able to win any other competition, not getting enough commissions, having problems with clients…but this is the normal life for an office. Up and down, always.

Paolo Emilio Belisario: Local, Global or Glocal. Almost’s 80% of your buildings are in Ljubljana. As you said in interviews “we are local”. How and how much the local context “contaminates” your projects? What are advantages of being “local”?

Bostjan Vuga: Slovenia has a very small territory and Ljubljana is a middle size European capital: it is not big. When we started it was a very good time: a young Country, a transitional period, people wanting something new, something different. There was a new energy in the Country. So to work here means we can take Ljubljana like a case study, because it is small. We can see and test what kind of urban and social effect our buildings can have in the city, in the environment. In a bigger city you can’t see these effects. Being local is a big benefit for us.

Paolo Emilio Belisario: Cause and effect. You always talk about “special concepts” of your office called “Formulas”. The word itself already suggests a kind of mathematical relationship present in creative process, a relationship of cause and effect. What is it?

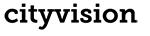

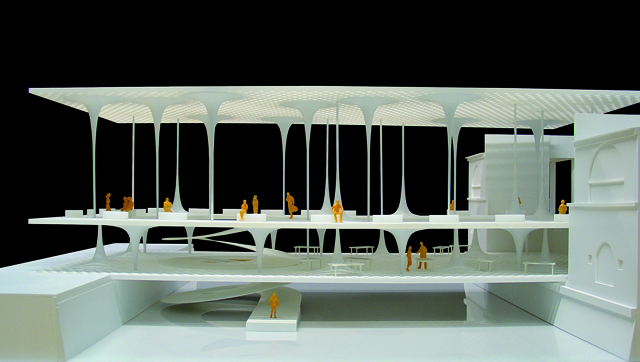

Bostjan Vuga:Formulas are “short phrases” we developed in our office during the last 12 years. Cinematic Structure, Vertical Hall, Optical Wall… these phrases are related both to an architectural element (example: structure) and to an effect of that element to user (example: cinematic). Cinematic Structure was the main formulas for the National Gallery. It is a structure settled to provide a cinematic effect of the space and generating a cinematic perception to the viewer. This is what I meant by effect of an architecture on the user. We also use Formulas to communicate in the office: we say ”let’s develop a vertical hall” or “this project should be develop around the vertical hall” (as for Chamber of Commerce and Industry). We developed 17 formulas and then we started using these Formulas together. In today’s project there is not such a clear distinction like in the past, but formulas are much more fused.

When we started we were much looking to external sources, images from fashion, now we are much using our previous projects as a source for development. I believe Formulas are our system for the evolution of the Office.

Paolo Emilio Belisario: City Vision. What happens instead in urban vision? Formulas are valid for cities too?

Bostjan Vuga: The same Formula can give rise to multiple products / buildings. Formulas are independent from the type of building, the location, the budget, the time of execution…or any other parameter that sets out the uniqueness of an architectural product. Formulas are intended to become generic phrases and to provide an easy to use tool for communicating architectural products. One Formula captures the character of an architectural product and its effect on the observer and user.

Paolo Emilio Belisario: The Future. In a video interview for AD you said that “the role of an architect should be to generate the new, to show how the future will be and how it can be built.” So how do you imagine the future?

Bostjan Vuga: I imagine the future very basic and very rudimentary: high development of technologies, that will become more invisible, more “nano”, less mechanical but more interactive and integrated. Technologies’ development won’t be demonstrated. We will experience an interface between us and something very basic like wild nature. We will feel the future but not see the future.

Paolo Emilio Belisario: Communication. Formulas are therefore also a tool of communication in the office, in discussions with the client and during public presentations. What about the Internet, social networks, media? What role they have in your work?

Bostjan Vuga: Communicating in architecture is always been present. In the beginning it was through books; then through books and magazine; now through books, magazine and internet and in the future will be something else.

In our work communication is a special project. If you don’t know how to communicate architecture you also don’t know how to build. We started the office; we realized some buildings, but then how to communicate with that? When and where the first exhibition should be done to influence the society? When we should do the first book and how it should look like?

Communicating architecture is not like a PR work, but it is much more transmitting ideas. Step A of your Venice CityVision Competition is all about communication, but step B is more important: how these 200 proposals can be communicated to influence the way of how a city like Venice can be transformed?

Our first book was called “3D > 2D: The Designers Republic’s adventures in and out of architecture” and it was a sort of antithesis of architecture’s monograph. We didn’t want to show the buildings, but we destroyed the buildings into a graphic language. Also, one exhibition we had was called “Sadar-Vugas spring summer 2000″ presenting our work like a fashion collection: we don’t do fashionable building, but we learned how to communicate building from fashion.

Paolo Emilio Belisario: Innovation. Still in a video interview for AD you said on communication: “Innovation means knowing how to produce and how to communicate”: to innovate you need to be able to communicate your ideas to customers, contractors and the public. In addition to communicating how we can really innovate our environment, the local context in which we live?

Bostjan Vuga: In order to be innovative in architecture you need to do it in a 3D space. Not virtual, but in the real space. This is what architecture can do and no one else can do. Innovating is to enable new experiences to people who come into the building; that are in physical interaction with it: so touching, feeling, smelling and seeing the space that we created. That’s it.

Paolo Emilio Belisario: History. Do you find limits in living and/or planning in historic cities like Venice or Rome? How do you think you can transform/re-design the historic cities?

Bostjan Vuga: The historical city is like a living organism that needs to be transformed. The worst thing that could happen to an historical city, all over the world, is to be frozen as a preserved area not allowing any changes in it.

Cities like Venice or Rome are multilayered cities where you can read traces of history. This makes those cities being really interesting. We should actually figure out possibilities for changing that would enrich and allowed a dynamic transformation of the city. I’m not saying that a city like that should be demolished or completely changed, but, why not finding specific areas in the historical core of Venice which could become the Venice of the XIII century? I mean if in Venice we can see buildings from the XVI century next to the XVII or XVIII century, why not seeing also the XIII century?

Of course there are limits, that’s why it is really important, not only for architects, to find criteria that would allow transformation in the historical centres, possibly finding some buildings with really less value then others to work with.

Related Posts :

Category: Article

Views: 4084 Likes: 0

Tags: bostjan vuga , sadar , slovenia , vuda

Comments:

Info:

Info:

Title: SADAR+VUGA

Time: 31 ottobre 2011

Category: Article

Views: 4084 Likes: 0

Tags: bostjan vuga , sadar , slovenia , vuda