PAPER BASTARDS by Emmanuele J. Pilia

step 0 : Prologo

The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic

When we talk about masochism, it is as if we talk about sadism: the only difference between the two categories is the subject that is mortified. It is mine or your flesh, mine or your individuality that is humiliated, violated, beaten, pierced, perforated. The sadist and the masochist are complementary to each other and together direct the process of mortification of the body. The true masochist is someone who refuses, rejects or ignores the organic nature of his body, and aspires to be “thing”. «Giving himself as something that feels and getting something that feels, this is the experience that is imposed to the contemporary feeling, an extreme and radical experience, yet it is the key to understanding the many and different manifestations of culture and art today» (p. 6). Mario Perniola’s The Sex Appeal of the Inorganic is, without doubt, the book that best investigates a contemporary masochistic feeling. The book also gives us a wonderful chapter on architecture: « Making architecture without constructing, philosophizing without building means transforming them into adventures, where we ventured with an expectation of extending, through the offering of themselves to a neutral and impersonal movement, the area of the visible and the thinkable» (p. 111).

Avviare un discorso sul masochismo equivale ad avvicinarsi alla tematica del sadismo: la reale differenza tra le due categorie è data unicamente dall’indirizzo della mortificazione di cui entrambi i poli si fanno referenti. È la mia o l’altrui carne, la mia o l’altrui individualità a essere umiliata, violata, percossa, attraversata, perforata. Le figure del sadico e del masochista sono tra loro complementari, e assieme offrono la possibilità di vettorializzare tale processo di mortificazione. Il vero masochista è l’individuo che rifiuta, ripudia o ignora la natura organica del proprio corpo, e aspira a farsi “cosa”. «Darsi come una cosa che sente e prendere una cosa che sente, questa è l’esperienza che s’impone al sentire contemporaneo, esperienza radicale ed estrema e che tuttavia costituisce la chiave per intendere tante e disparate manifestazioni della cultura e dell’arte attuali» (p. 6). Il Sex appeal dell’inorganico di Mario Perniola è senza dubbio il libro che meglio indaga ed esprime il sentire masochista contemporaneo, in grado anche di offrire a sacrificio un meraviglioso capitolo all’architettura: «Fare architettura senza costruire e fare filosofia senza edificare significa trasformarle in avventure, in viaggi in cui ci si arrischia con l’attesa di estendere, attraverso l’offerta di se stessi a un movimento neutro e impersonale, l’ambito del visibile e del pensabile» (p. 111).

step 1 : Protesi

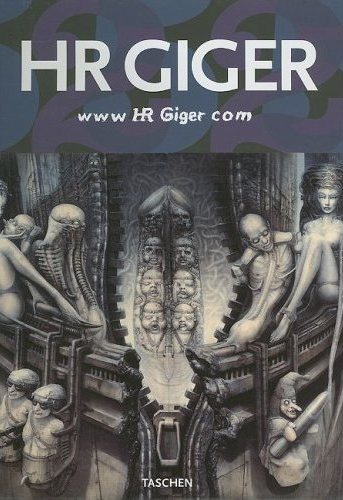

HR GIGER published by Taschen

The work of Giger travels in the same direction of Perniola. In his works, he casually piled bodies fused together. These bodies, which are made shiny with a thin layer of body fluids, lose their individuality. Every scrap of conscience, that animated the flesh, is canceled by the silence of the spaces represented. It’s as if every inch of skin, every penis, every vagina, each breast that fills the portraited scenes, were still able to feel, to fully enjoy the pain that begrimes their lives until the next configuration. In HR GIGER, published by Taschen, is reported a comment by Georg Schmid about “Picture in the mirror”: «The author of this framework suffers from suicidal mania and causes the same kind of disturbance to other persons» (p. 7). I disagree with his opinion. He fails to grasp the vitality with which Giger combines guts to mufflers and bolts. Schmid’s error is anthropocentrism, which overlaps the existence of consciousness to “bare life”, thereby denying the right to continuity of existence between iron and flesh. It is easy to find continuity between Giger and Lars Spuybroek. In fact, the work of Spuybroek focuses on the use of architecture as a proprioceptive prostheses, an interaction between space and body that also considers the appendages of cyberspace as an extension of the building as is that of human skin and organs. As the tangle of legs and penises form the structures of sentient Giger’s paintings, so the architecture of Spuybroek is a continuation of the body which increases the user’s physical, intellectual, sensory and cognitive capacity, thus modifying the action and individual thinking. Known mainly for his projects, Spuybroek has been known to have a vast theoretical capacity, and his book Architecture of continuity is the proof. The book is presented as a collection of his most important essays published over the years – with some interesting unpublished ones – and it is still innovative. «Movement can be fluent only if the skin extends as far possible over the prosthesis and into the surrounding space, so that every action takes place within the interior of the body, which no longer acts consciously but relies completely on “feeling”» (p. 34).

L’intera opera dell’artista Hans Ruedi Giger può essere descritta come un lungimirante percorso visivo che viaggia nella stessa direzione intrapresa da Perniola. Il suo lavoro consiste, infatti, nell’ammucchiare corpi fusi tra loro alla bene e meglio, i quali, resi lucenti da un sottile strato di fluidi corporei, perdono ogni individualità. Qualsivoglia brandello di coscienza, che un tempo animava quelle carni, viene annullata dal gelido silenzio che circonda gli spazi raffigurati. Eppure è come se ogni centimetro di pelle, ogni fallo, ogni vagina, ogni mammella che colma le scenografie ritratte fosse ancora capace di sentire, di godere pienamente del dolore che lorda la loro esistenza fino a che non sarà completata l’ennesima configurazione. Nell’autobiografia HR GIGER, edita dalla Taschen, viene riportato un commento di Georg Schmid all’opera Immagine allo specchio: «L’autore di questo quadro soffre di mania suicida e causa lo stesso tipo di disturbo anche ad altre persone» (p. 7). Non riesco ad essere d’accordo con la sua opinione, che non riesce a cogliere la traboccante vitalità con cui Giger accosta budella a marmitte e bulloni. L’errore di Schmid è un eccessivo antropocentrismo, che sovrappone erroneamente la nozione di “coscienza” alla nuda vita, negando così il diritto di esistenza alla continuità tra ferro e carne. È difficile non trovare una qualche linea di continuità tra il lavoro di Giger e quello di Lars Spuybroek. L’opera di Spuybroek si concentra, infatti, su un utilizzo dell’architettura come protesi propriocettiva, sull’interazione tra spazio e corpo che considera anche le appendici del cyberspazio come estensioni, tanto dell’edificio, quanto della pelle e degli organi umani. Come l’intreccio di cosce e falli formano le strutture senzienti delle opere dell’autore svizzero, così per Spuybroek l’architettura è a tutti gli effetti una prosecuzione del corpo del fruitore, che amplifica le potenzialità fisiche, intellettuali, sensoriali e cognitive dell’individuo, modificando di conseguenza l’agire e il pensare individuale. Conosciuto principalmente per i suoi progetti, Spuybroek ha dimostrato di avere delle notevoli capacità teoretiche, e il suo testo Architecture of continuity è senza dubbio una più che degna dimostrazione. Presentato come una raccolta dei principali saggi pubblicati negli anni – con qualche interessante inedito – il testo dell’olandese si pone su un piano teorico ancora oggi innovativo, particolarmente aderente ai principi transumanisti, pienamente concentrato sull’esperienza della carne. «I movimenti possono essere fluidi solo se la pelle si estende il più possibile alla protesi e all’interno dello spazio circostante, così che ogni azione abbia luogo all’interno del corpo, il quale non compie più movimenti coscientemente ma basandosi completamente sul “sentire”» (p. 34).

step 2 : Una natura artificiale

HYLOZOIC GROUND liminal respoansive architecture

Philip Beesley

The work of Perniola, Giger and Spuybroek is joined by a peculiar element of contemporaneity: the ratio between body and thing. If on one hand, our time is obsessed with the idea of sentient thing, on the other hand the body, understood as zoé is increasingly being pushed towards it’s becoming a thing. This theoretical approach derives from that ancient doctrine that sees matter a dynamic energy, called hylozoism, made from the greek word h••le, “matter”, and zòon, “life”. In this regard, the work of Philip Beesley gives a very original interpretation: Hylozoic Ground. Liminal Responsive Architecture is the fine catalog with which the Canadian architect signs his presence at the Venice Biennale of Architecture in 2010. The text illustrates the sense of a sort of silicon jungle that mimics the behavior of insects and tropical plants. Strange fluid flows from an ampoule to another, while the leaves lift their mantle to the passage of unsuspecting visitors. Lights and sounds alternate each other as an instinctive reaction to the behavior of those who have the courage to submit themselves to this absurd vegetation, diluting the border between derma and polymers: every action gets a reaction from the installation, creating an empathy that leads us to a primordial state of wonder. The same surprise emerges in the series “Community Gardens” by Giacomo Costa, where huge infrastructures left in a state of degradation by a civilization that is now extinct, is waiting to be reabsorbed by nature. But colossuses of concrete and highways remain which is typical of a separated from the tree and shrub species, which do not contribute to the fall of firmitas and utilitas which is typical of a ruin. The ruin is an architecture accessible only as “venustas”, free from other uses that is not ones own “thought” about “time”. On the other hand, if the ruins were left exposed to the dissolving vegetal nature, they would lose their position of ruin as “pure venustas”. The book edited by Luca Beatrice, “Giacomo Costa: the chronicles of time”, explains the work of the Florentine artist, emphasizing the frailty of the human condition that is pleased with its miserable weakness.

Il lavoro dei tre autori citati, Perniola, Giger e Spuybroek, è unito da un elemento peculiare della contemporaneità, da un doppio movimento che ha il corpo e la cosa come baricentro. Se da una parte, infatti, il nostro tempo è ossessionato dell’idea della cosa senziente, dall’altro, invece, il corpo, inteso come zoé, è sempre più spinto verso il proprio farsi cosa. Questa deriva teorica, che ha preso piena coscienza di sé solo a partire dagli ultimi trent’anni, è erede di quell’antica dottrina che concepisce la materia come un’energia dinamica e vivente, chiamata ilozoismo, termine composto dal greco h••le, “materia”, e zòon, “vita”. Al riguardo il lavoro di Philip Beesley offre una lettura particolarmente originale: Hylozoic Ground. Liminal Responsive Architecture è il bel catalogo con cui l’architetto canadese firma la propria presenza alla Biennale di Architettura di Venezia del 2010. Il testo ben illustra il senso di un opera che cerca di darsi come una sorta di giungla silicea, imitante il comportamento di insetti e piante tropicali. Strani fluidi trapassano da un’ampolla all’altra, mentre quelle che appaiono foglie sollevano il proprio manto al passaggio degli ignari visitatori. Luci e rumori si alternano come reazione istintiva ai comportamenti di chi ha il coraggio di inoltrarsi tra le foglie di questa assurda vegetazione, diluendo il confine tra derma e polimeri: ogni gesto riceve una reazione dall’installazione, creando così un rapporto empatico che ci riconduce a uno stato di stupore primordiale. Lo stesso stupore che emerge nella serie Community Gardens di Giacomo Costa, dove enormi infrastrutture, lasciate al degrado da una civiltà ormai estinta, attendono il riassorbimento al dominio di una natura ancora circoscritta ai margini. Ma colossi di cemento e autostrade incomplete, nell’atto del proprio farsi rovina, restano dichiaratamente separati dalle specie arboree ed arbustive della flora spontanea, la quale non contribuisce alla caduta di firmitas ed utilitas, tipica del rudere. Questo, così, si presenta come massa architettonica fruibile unicamente per la propria pura venustas, incontaminata da altri usi che non sia la propria riflessione sul sospeso. D’altra parte, se i rottami esposti fossero lasciati dissolvere dall’aggressione vegetale, essi perderebbero la propria carica di rovina come pura venustas. Il libro di Luca Beatrice, Giacomo Costa: the chronicles of time, illustra compiutamente il lavoro dell’artista fiorentino, facendo emergere sopra ogni altra cosa la caducità della condizione umana, che si compiace della propria infida debolezza.

Related Posts :

Category: Article

Views: 1736 Likes: 0

Tags: Giger , HR GIGER , Lars Spuybroek , Mario Perniola , PAPER BASTARDS , Sex Appeal of the Inorganic , Taschen

Comments:

Info:

Info:

Title: PAPER BASTARDS by Emmanuele J. Pilia

Time: 24 maggio 2012

Category: Article

Views: 1736 Likes: 0

Tags: Giger , HR GIGER , Lars Spuybroek , Mario Perniola , PAPER BASTARDS , Sex Appeal of the Inorganic , Taschen