Devouring architecture: Ruskin’s insatiable grotesque

text by Paulette Singley

Despite the perils involved with naming historical origins – the comfort of a stable beginning, the temptation of clean chronological divisions, and the promise of positive progression – the grotesque thrives upon and embodies the dilemma of beginnings and openings. According to Giorgio Vasari, who documents its inaugural birth, the grotesque begins when it emerges from out of the subterranean caverns of Nero’s Domus Aurea and breaks into the light of Renaissance art theory. Vasari narrates this discovery in the life of Morto da Feltro: Morto restored the painting of grotesques in a manner more like the ancient than was achieved by any other painter, and for this he deserves infinite praise, in that it is after his example that they have been brought in our own day, by the hands of Giovanni da Udine and other craftsmen, to the great beauty and excellence that we see. For, although the said Giovanni and others have carried them to absolute perfection, it is nonetheless true that the chief praise is due to Morro, who was the first to bring them to light and to devote his whole attention to paintings of that kind, which are called grotesques because they were found for the most part in the grottoes of the ruins of Rome.[11]

As the aftermath of this momentous birth, extensive scholarship on the grotesque in art and literature has been developed to such an extent that it would seem possible to discuss this subject without repeating, ad infinitum, Vasari’s account of its origins.[12] The etymon of grotto, buried within the grottesque, however, compels the repetition of Raphael’s legendary descent into what has become an archetypal cave, thereby reconstituting what emerged as a hybrid ornamental motif composed of diverse animal, vegetable, and architectural fragments into the conundrum of architectural origins and the crisis of primary parturition.[13] While Vitruvius censures new fashions in Roman wall painting as early as the first century A.D. – a fashion eventually identified as the third Pompeiian style – and confirms that the concept existed well before its incipient discovery and naming, the compulsion to repeat the root meaning, the etymological trap of grotto-esque, renders a chthonic descent into a myth of eternal return: every time we invoke the grotesque we must return to the cave. In this sense, then, the grotesque is both a stylistic category and the multitude of bizarre fantasies released when exploring architecture’s psychological underground. Thus a genealogy of grotesque architecture locates its Ursprung in Nero’s Domus Aurea. It would encompass both the wall paintings and the jewel-encrusted, rotating dining hall. The progeny of the Domus would include not only the more famous examples of Leonardo’s caves, Michelangelo’s tombs, and Piranesi’s carceral visions, but also such variants as the camera obscura/grotto in Alexander Pope’s garden, the scabrous entry to Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s saltworks at Chaux, or the hollow caverns of Jean-Jacques Lequeu’s “Gothic House.” More recent explorations would involve such diverse architectures as the crooked grottoes of accumulated detritus in Kurt Schwittters’s Hannover Merzbau or the crocheted tissues of wire, bone, and beads in Jennifer Bloomer and Nina Hofer’s “Tabbies of Bower.” In what might be construed as a hysterical list of references marshaled toward describing the diverse blossoms nestled in the captivating vines of the grotesque, Mark Taylor alludes to a number of post-Vasarian theories; Julia Kristeva’s abjection, Derrida’s cryptonomy, Georges Bataille’s informe, Martin Heidegger’s “origins,” Immanuel Kant’s “sublime,” Sigmund Freud’s unheimlich, Mikhail Bakhtin’s “carnival,” and Gianni Vattimo’s “weak thought” all explore cavernous margins of thought that insinuate a grotesque architecture. Having evolved from a specific term referring to an ornamental device that allayed the horror vacui of Renaissance artists to a vague expression of something that is fantastically absurd or even sickening, the grotesque – as demonstrated by the work of Schwitters or Bloomer – likewise has the power to expand its proper boundaries and entirely to engulf the edifice.

Within the manifold descriptions of absorption, rupture, and excess that characterize the grotesque architectural body, John Ruskin’s etiology of La Serenissirna in The Stones of Venice engages this expansion of meaning from an ornamental program to a delirious mental state that produces absurd and sickening artifacts. Ruskin passes into the body of grotesque architecture through an ornamental mouth on the church of Santa Maria Formosa that speaks to him of Venice’s fall into an “unscrupulous pursuit of pleasure,” to the extent that the architecture of the Venetian Renaissance is among the lowest and basest ever built by the hands of men, being especially distinguished by a spirit of brutal mockery and insolent jest, which, exhausting itself in deformed and monstrous sculpture, can sometimes be hardly otherwise defined than as the perpetuation in stone of the ribaldries of drunkenness. (11: 135)[14]

In the chapter “Grotesque Renaissance,” found in the third volume of The Stones, titled “The Fall,” from which this passage was taken, Ruskin allegorizes the decline of the Venetian Republic through two elaborate legends buried within the church: one being its foundation and the other being the emergence of the Festival of the Twelve Maries.

Ruskin writes: The Bishop of Uderzo, driven by the Lombards from his bishopric, as he was praying, beheld a vision of the Virgin Mother, who ordered him to found a church in her honour, in the place where he should see a white cloud rest. And when he went out, the white cloud went before him; and on the place where it rested he built a church, and it was called the Church of St. Mary the Beautiful [Santa Maria Formosa], from the loveliness of the form in which she had appeared in the vision. (11:137)

He reports that the church was consecrated in the mid-seventh century, rebuilt in 864 and enriched with relics, rebuilt again after a fire in 1105 (or 1175 according to another source Ruskin mentions) and stood until 1689 when it was destroyed by an earthquake only to be restored by a rich merchant named Turrin Toroni. Despite conflicting historical accounts of Santa Maria Formosa’s history, to Ruskin “all that is necessary for the reader to know is, that every vestige of the church in which the ceremony took place was destroyed at least as early as 1689; and that the ceremony itself, having been abolished in the close of the fourteenth century, is only to be conceived as taking place within the more ancient church, resembling St. Mark’s” (11: 138). He directs the reader’s attention to “the contrast between the former, when it had its Byzantine church, and its yearly procession of the Doge and the Brides; and the later, when it had its Renaissance church ‘in the style of Sansovino,’ and its yearly honouring is done away” (11: 138).

The yearly procession was a Venetian custom that brought about the legendary attack and rescue of brides in the year 943. During medieval times, nobles were allowed to wed one day a year, in a sacrament between god and man where “every eye was invoked for its glance and every tongue for its prayers” (11:139). Ruskin’s friend, the poet Samuel Rogers, describes a typical bride as covered with a “veil transparent as the gossamer,” which “fell from beneath a starry diadem” and over a jewel on her dazzling neck.[15] As per medieval legend, in the year 943 these jewels enticed Triestine pirates to enter the church of St. Pietro di Castello, to attack the laity, and to abduct the virgin brides. In response to this attack, the casseleri, a group of trunk makers or carpenters from the parish of Santa Maria Formosa, rescued the brides and their dowry chests. The possible translation of casseleri into “casket makers” intrigues Ruskin, who writes “if, however, the reader likes to substitute ‘carpenters’ or ‘house builders’ for casket-makers, he may do so with great reason,” thereby placing the building tradesmen at the center of the brides’ rescue and the restoration of social order (11:143).[16]

As a reward for their bravery the Doge promised to visit the church of the casseleri every year, so that “the festival of the 2nd of February, after the year 943, seems to have been observed only in memory of the deliverance of the brides, and no longer set apart for public nuptials” (11: 140).

From this event supposedly emerged the Festival of the Twelve Maries, a three-day-long procession from San Marco’s Cathedral to Santa Maria Formosa that featured as its central ornament twelve maidens dressed in silver and gold.

In a more detailed account of the festival than Ruskin provides, Edward Muir explains that on 31 January (the date for parish priests to solemnize all betrothals from the previous year) the prince and the commune of Venice, in an act of public charity, sponsored weddings for twelve “deserving but poor” girls by offering them dowries and adorning them in gems.[17]

It was both the dowries and the girls that attracted the Triestine pirates to enter the cathedral of San Pietro di Castello and make off with these treasures. According to Muir, while “the rape of the Venetian and the Sabine women are both myths concerned with the problem of preserving group fertility,… the Venetian account emphasized the protective, peaceful, inward-looking order provided by a strong cohesive community.”[18] The date attributed to the retrieval of the brides and their dowries, 2 February, corresponded with the day of the Purification of the Virgin, or Candlemas, a ceremony commemorating Mary’s postpartum purification and celebrating divine motherhood.[19]

Despite the fact that “every feature of the surrounding scene which was associated with that festival has been in succeeding ages destroyed” Ruskin nonetheless argues that the spot is still worth a pilgrimage in order to receive a painful lesson (11: 144).

He advises the reader to recall the ancient festivals to the Virgin where the daughters of Venice knelt yearly, before examining “the head that is carved on the base of the tower, still dedicated to St. Mary the Beautiful.” It is

A head, – huge, inhuman, and monstrous, – leering in bestial degradation, too foul to be either pictured or described, or to be beheld for more than an instant, yet let it be endured for that instant; for in that head is embodied the type of evil spirit to which Venice was abandoned in the fourth period of her decline; and it is well that we should see and feel the full horror of it on this spot, and know what pestilence it was that came and breathed upon her beauty, until it melted away like the white cloud from the ancient fields of Santa Maria Formosa. (11: 144-45)

After he isolates this particular head from the multitude infesting Venice, Ruskin lists the most contaminated buildings and, rather cannily, insists that we, too, should visit them. His topography of degenerate architecture diverts the tourist’s itinerary away from visiting the most beautiful or noteworthy sites into a survey of the most hideous. His unique processional route leads us from the churches of San Moist (by Alessandro Tremignon in 1668), of Santa Maria Zobenigo (by Giuseppe Sardi in 1680), of St. Eustachio (also known as San Stae, by Domenico Rossi in 1709), and of the Ospadeletto (by Baldassare Longhena in 1674); then to the Palazzo Corner della Regina (by Domenico Rossi in 1724-27), the Palazzo Pesaro (also by Longhena, begun in 1652) and, finally, to the Bridge of Sighs (by Antonio Contino in 1600).[20] Each of the churches is encrusted with excessive secular ornamentation that swallows the facades they are supposed merely to embellish with sacred images. In other words, where the ornamental program should subordinate itself as an extrinsic element or frame to the larger aesthetic representation of the building, here it consumes the building’s face as a leprous growth that feeds off of stony flesh.

By isolating the head on Santa Maria Formosa from the larger body of grotesque ornament, Ruskin opens in The Stones of Venice a tangible fissure, toward which Mark Wigley has pointed me, a fissure that we are about to enter. First, apart from Ruskin’s historical excursus of the virgin brides’ abduction and the Virgin Mother’s appearance that motivates his heated attack, the facade of Santa Maria Formosa appears restrained when compared with the other buildings just listed and the lonely head appears to be rather ordinary. As a central antagonist within The Stones, the head occupies a position in the book that its visage on the church hardly seems to merit.

Ruskin initiates his discussion on the grotesque Renaissance in an earlier chapter, titled “The Nature of Gothic,” where he simply tempts us with a quick allusion to this subject and then defers his explanation until the third volume.[21]

Not only does this deferral allow him to maintain the chronological sequence necessary to write the history of a rise and fall, it also heightens his climactic outrage against the Renaissance perversion of art and society. In fact, as his vivid language betrays, the grotesque is one of Ruskin’s great passions.[22]

The open mouth of the ornamental head acts as a closure to both The Stones and the Renaissance, provoking the question as to why, of all the innumerable open sores that may be found in Venetian architecture, has Ruskin directed such energy toward censuring this particular head and then failing to represent it? Despite his distinct instruction to gaze at the degraded image, if only for an instant, Ruskin nonetheless expresses profound ambivalence toward our looking at this object that is too hideous to be either pictured or described. Instead of illustrating his text with the head on Santa Maria Formosa, he substitutes a head from the foundation of the Palazzo Corner Regina “made merely monstrous by exaggerations of eyeballs and cheeks,” as an example of the base grotesque; and he compares it to another example of the base grotesque, a Gothic lion symbol of Saint Mark from the Castelbarco Tomb in Verona (11: 190). In this struggle between attraction and repulsion, iconophobia and iconophilia, Ruskin admonishes us to set our eyes briefly upon an image that is too lurid even for him to render visible in drawings or in words. Despite the potential to draw from Ruskin’s publication as a guidebook to Venice, the primary role of The Stones was as a discourse on English architecture, culture, and mores; and it is this polemic of reform that severs Ruskin’s text from the physical exigencies of Venice.

Or does it? Despite his claim that the head is too vile even to describe in words, Ruskin actually does convey enough illustrative details – such as huge, inhuman, monstrous, and leering – for us to generate a vivid mental picture that might even surpass the horror of the actual head. Furthermore, he describes the typical grotesque face as a tongue protruding from an expression of sneering mockery. And, finally, despite his promised silence, he cannot contain himself from exclaiming that in the head on Santa Maria Formosa “the teeth are represented as decayed” (11: 162) His description, however guarded, inevitably overflows the boundaries of representation. Ruskin’s advice actually to visit Venice operates as a rhetorical device that invites the reader on an imaginary voyage; thus he covers his argument of social reform with the innocent jacket of a tourists’ guidebook. If Ruskin had implored us never to set our eyes upon the profane image, he would risk enhancing its erotic appeal by thus veiling it. Instead, with an expert sleight of hand, he encourages us to examine an object that is entirely unavailable to our gaze – a skillful maneuver that also allows him to dodge the crisis of representing the disgusting or the ugly. But, most important, by refusing to render the head visible in The Stones, Ruskin covers our naked eyes with his written hand.

While my textual exegesis is overdetermined, it could not possibly match the hyperbolic intensity of Ruskin’s words. Three volumes are filled with what Tony Tanner describes as “unblushing rhapsodic flights” of prose and as “extremely vituperative, even venomous” writing.[23]

If we follow Stephen Bann’s argument, both the literary tradition of ekphrasis, the classical convention for writing about art, and Horace’s notion of Ut pictura poesis, or, as a painting so in poetry, are central to our discussion of Ruskin and the grotesque. Bann explains that ekphrasis is a genre of writing, parasitic upon a work of art, “dependent first of all on the risky presumption that the visual work of art can be translated into the terms of verbal discourse without remainder.”[24]

While Bann argues that verbal descriptions cannot cover all aspects of an artwork and, consequently, must leave something out, I would expand this discussion to argue that it is likewise possible for verbal description to overflow the limits of the artwork and to engulf it in a language of surplus. While insufficient ekphrasis is a danger, so too, are superfluous descriptions, which threaten the status of the artwork with a “devouring language.”[25]

When writing amplifies to an excessive extent the content of a work of art, it can swallow the work whole. While it would be tempting, and even meaningful, to argue that Ruskin’s writing mirrors the grotesque subjects of his discussion, his omission of the head in his publication allows him to circumvent neatly the possibilities of his own excessive prose. Insofar as Geoffrey Gait Harpham concludes that “the ambivalent presence of meaning, within the ostensibly meaningless form constitutes the real threat, and the real revolution, of grottesche,” Ruskin responds to this “semiotic ambivalence,” with his disturbed treatment of the head.[26]

The oscillation between lack and surplus that structures the paradox of representing the ugly also applies to descriptions of the terrifying; in both cases, to reproduce/imitate in words the hideous or terrifying objects is to become them. The conflictual relations sufficiency/insufficiency, surplus/ deficit, abundance/shortage, in terms of representation, serve well to summarize the dilemma Kant encounters when writing about the sublime: Where fine art evidences its superiority is in the beautiful descriptions it gives of things that in nature would be ugly or displeasing. The Furies, diseases, devastations of war, and the like can (as evils) be very beautifully described, nay even represented in pictures. One kind of ugliness alone is incapable of being represented conformably to nature without destroying all aesthetic delight, and consequently artistic beauty, namely, that which excites disgust.[27]

Similarly, it would seem that Ruskin actually writes of the sublime when comparing the noble with the ignoble workman, because the latter “may make his creatures disgusting but never fearful” (11: 170).

Disgust and fear, grotesque and sublime. To emphasize this distinction Ruskin calls forth the Furies to describe the worker who is not inspired by the sublimity of divine terror, dividing the proper subjects of fear into modes of artistic temperament: first, predetermined or involuntary apathy, second, mockery, and third, diseased and ungoverned imaginativeness (11:166). Regarding involuntary or predetermined apathy, he distinguishes between the false and the true grotesque:

In the true grotesque, a man of naturally strong feeling is accidentally or resolutely apathetic; in the false grotesque, a man naturally apathetic is forcing himself into temporary excitement. The horror which is expressed by the one, comes upon him whether he will or not; that which is expressed by the other, is sought out by him and elaborated by his art. (11: 168)

In this respect, the artisan of the false grotesque “never felt any Divine fear; he never shuddered when he heard the cry from the burning towers of the earth, ‘Venga Medusa: si lo farem di smalto.’ He is stone already, and needs no gentle hand laid upon his eyes to save him” (11:169).[28]

In this passage that Ruskin borrows from Dante’s Inferno, the gentle hand belongs to Virgil, who is protecting the younger poet from the Gorgon’s petrifying gaze.[29]

Thus, when the Furies, screaming from the burning tower, cry, “Let Medusa come and we’ll turn him to stone,” it is, in fact, the poet’s hand that draws the protective veil over the observer’s eyes and encrypts the image within words. But in The Stones, Ruskin covers our view with a veil as transparent as gossamer, and in so doing actually endows the head with libidinal energy. In other words, the failure of Ruskin’s iconophobia to construct the absence of compelling images as free from the seduction of absent images weaves a veil of desire. This, in a nutshell, is the crisis of representation that the grotesque discloses when it intersects the rhetorical program of ekphrasis.

Venga Medusa: silo farem di smalto. In Sigmund Freud’s frequently cited essay “Medusa’s Head,” “To decapitate = To castrate.” The terror of Medusa is the fear of castration linked to vision. This fear “occurs when a boy… catches sight of the female genitals… surrounded by hair” and discovers the missing penis.[30]

Both the head of Medusa and the vulva are apotropaic, or counterphobic, objects to the male gaze: when openly displayed they produce a feeling of horror or petrifaction in the male viewer. And indeed, Ruskin writes, “it is not as the creating, but as the seeing man, that we are here contemplating the master of the true grotesque” (11: 169). While Freud refers to Rabelais’s story of “how the devil took to flight when the woman showed him her vulva,” in a historical account of apotropaism in action during the 1848 revolution, Parisian women were known to lift up their skirts and expose their pudenda as a defensive tactic.[31]

Regarding the consequences of such an exposure, Ann Bergren explains that after the male flees in fright, he attempts to “repress the wound without a trace.”[32]

In Ruskin’s case, when he covers the swollen lips of the severed head with his own textual surplus he both erases and enhances the wound. The possibilities of an apotropaic architecture suggest an application of Freud’s analysis to Ruskin’s grotesque object of desire, now viewed as a vagina that leers in bestial degradation. Rather than a castration, it is a grotesque cave or vagina dentata from which effuses the liquid succubus of a perforated interior that turns the male citizens of Venice into Ruskin’s stones while endowing the women with phallic power. A form of invagination that refers to multiple folds and an open interior, Ruskin’s grotesque overlaps the intrauterine space of architectural origins: no longer the inviolate origins of virgin betrothal and immaculate conception, but alluding to the “necessity” of postpartum purification.

The grotesque also overlaps the “uterine” disease of hysteria and the implications of mental disorders to which, according to Ruskin, all artists are subject. If we return to the question of apathy discussed above, Ruskin himself describes the grotesque as belonging in part to diseased and ungoverned imaginativeness:

The grotesque which comes to all men in a disturbed dream is the most intelligible of this kind, but also the most ignoble; the imagination, in this instance, being entirely deprived of all aid from reason, and incapable of self-government. I believe, however, that the noblest forms of imaginative power are also in some sort ungovernable, and have in them something of the character of dreams; so that the vision, of whatever kind, comes uncalled, and will not submit itself to the seer, but conquers him, and forces him to speak as a prophet having no power over his words or thoughts. Only, if the whole man be trained perfectly, and his mind calm, consistent, and powerful, the vision which comes to him is seen as in a perfect mirror, serenely, and in consistence with the rational powers; but if the mind be imperfect and ill trained, the vision is seen as in a broken mirror, with strange distortions and discrepancies, all the passions of the heart breathing upon it in cross ripples, till hardly a trace of it remains unbroken. (11: 178-79)[33]

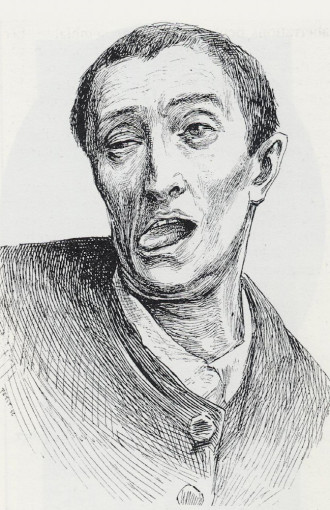

Although the image of the broken mirror reflects the interior of Alexander Pope’s garden grotto, lined with shards of sparkling glass, I have cited this passage for its classical allusion to artistic madness and the symptomology of the grotesque mind that produces it. While the head of Santa Maria Formosa, in Ruskin’s analysis, reflects the mind of a suffering artist, it is Jean-Martin Charcot, writing in Les Difformes et les malades dans l’art of 1889, who directly links the head with the visage of a male hysteric and, in so doing, returns the grotesque from the fantasies of disturbed minds to the field of natural representation. So important is the head to the argument Charcot proffers in this publication that he opens the first chapter, titled “Les Grotesques,” by explaining that the grotesque mask on the Church of Santa Maria Formosa is his point of departure and by citing Ruskin’s powerful description, quoted above, from The Stones of Venice: “A head, — huge, inhuman, and monstrous, — leering in bestial degradation, too foul to be either pictured or described, or to be beheld for more than an instant.”[34]

Charcot sees the signs of convulsion in works of art as representing actual physiological disturbances. While artists may idealize and normalize their subjects, they also serve to decipher deformities into pathologies. As Georges Didi-Huberman writes, The work of art interprets the symptom in the sense that it reproduces it. This is the case of the famous grotesque mask from the Church of Santa Maria Formosa in Venice, where Charcot recognized none other than a ‘facial spasm of a special nature, often found in male or female hysteric subjects with a semiparalysis of the limbs, and exhibiting such distinctive characteristics that it is impossible to confuse it with any other spasmodic facial disorder.’ Charcot names it hemispasme glossolabie hysterique, and having it ‘in front of his eyes at Salpetriere,’ has Richer jointly engrave the Venetian mask and the portrait of one of his hysterical patients: as two ‘interpretations’ of the same role, of the same form.[35]

Charcot specifically aligns Ruskin’s head with the physical etiologies of hysteria, traditionally a female malady, now located in the male face. And while this reproduction of the head on the church of Santa Maria Formosa is a striking analog to Ruskin’s Stones, Charcot offers even further research on the Venetian Renaissance in Les Demoniaques dans l’art, where he analyzes a reproduction of Vittore Carpaccio’s painting Miracle of the True Cross that he titles “Le Patriache de grade delivre un demoniaque”:

The scene occurs on the banks of the Grand Canal of Venice, in the ground floor of a palazzo. Here is a mise-en-scene ably arranged to strike the imagination of the people, and which permits a large number of dignitaries to assist the miracle. At the foot of the palazzo, the crowd is already numerous; it is continually enlarged by the curious who arrive by water, and, in the distance, by the procession crossing the bridge. The Grand Canal is covered by gondolas. Within the loggia, surrounded by clerics and clergy holding large altar candles, a young boy is in torment; his mouth is open, his head is bent back, and turned to one side. His appearance is more one of a young choreic, or of one showing the symptoms of the dance of Saint-Guy, than a patient in the grip of a hystero-epileptic seizure. The patriarch presents him the cross.[36]

Charcot finds something close to the symptoms of epileptic hysteria, characterized by an open mouth, within Carpaccio’s depiction of an exorcism. The thin line between art and reality that Charcot observes haunted Ruskin, who had proposed writing a complete guide to Carpaccio’s work and who obsessed on the likeness between St. Ursula and the object of his affections, Rose La Touche, to the brink of his own madness.[37]

The open and salivating mouth of Carpaccio’s “hysteric,” metaphorically linked to a dyspeptic stomach and fiatulent anus, describes a grotesque body gorging in carnival inversion and excessive appetite. We might recall that the elaborate dining hall of Nero’s Domus Aurea was precisely such a site for feasting and feeding. A strong proponent of the potential for revolutionary transgressions inspired by Rabelais’s carnival, Mikhail Bakhtin describes the grotesque as walls turned to flesh in a world where the human body is used as a building material: where we can no longer distinguish the architectural boundaries between body and building, inside and outside, frame and subject. Quoting Rabelais’s character Panurge from Gargantua and Pantagruel, Bakhtin describes a delirious reversal of body and building parts: “I have observed that the pleasure-twats of women in this part of the world are much cheaper than stones, therefore the walls of the city should be built of twats.”[38]

In Bakhtin’s grotesque carnival the lower apertures of waste reach into the upper regions of taste through a mouth, that, when opened, reduces the face to a gaping orifice and also transforms Ruskin’s masking of the head into the writing-over of the oral capacity. If, as Bakhtin argues, the grotesque body may be translated into an architecture of gaping passages and tumescent towers, the head on Santa Maria Formosa engages in a dialogue with the campanile, where the mingling of phallic and vaginal topoi borders on fornication. Let us recall, too, that this was the only church in Venice dedicated to the Virgin, the legendary retrieval of the brides and their little boxes.[39]

Thus this particular site represents what happens when voluptuous desire erodes the fraternal bonds of the control of reproduction through marriage.

From pageants dedicated to sharing a communal Eucharist placed upon tongues that spoke the word of the Lord, to the festival’s transubstantiation into moist tongues licking loose lips, Ruskin marks the specific moment of Venetian decline with the death of the Doge Tomaso Mocenigo in 1423 and the ensuing year of festival. From then onward, the Venetians “drank with deeper thirst from the fountains of forbidden pleasure and dug for springs, hitherto unknown, in the dark places of the earth” (11: 195). Ruskin’s rather oblique reference to digging invokes the etymological origins of the grotesque, an archaeology that takes us inside the cavern at which we have thus far only gaped.

Given the linguistic dilemma of discussing the grotesque without referring to its archetypal origins, Walter Benjamin also succumbs to the compulsion to repeat:

The discovery of the secret storehouse of invention is attributed to Ludovico da Feltre, called ‘il Motto’ because of his ‘grotesque’ underground activities as a discoverer. And thanks to the mediation of an anchorite of the same name (in E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Die Serapionsbruder), the antique painter who was picked from Pliny’s much discussed passage on decorative painting as the classic of the grotesque, the ‘balcony-painter’ Serapion, has also been used in literature as the personification of the subterranean-fantastic, the occult-spectral. For even at that time the enigmatically mysterious character of the effect of the grotesque seems to have been associated with its subterraneanly mysterious origin in buried ruins and catacombs. The word is not derived from grotta in the literal sense, but from the ‘burial’ in the sense of concealment — which the cave or grotto expresses. The enigmatic was therefore part of its effect from the very beginning. For this the eighteenth century still had the expression das Verkrochene [that which has crept away]. Winckelmann’s position is not so very far removed from this. However severely he criticizes the stylistic principles of baroque allegory.[40]

I will close with Benjamin’s opening in the ground. The chthonic journey into the crypt and its originary status as architecture inhabits Ruskin’s text as “the subterranean fantastic” and” the occult-spectral.” By entering the grotto and transgressing the Vitruvian canon of propriety and mimesis in representation, late Renaissance artists ruptured the continuity between cinquecento humanism and Roman classicism by liberating the free and inventive license that the grotesque signified.[41] Ruskin, unlike our previous litany of theorists, does not directly return us to the cave through Vasari’s originary account. Rather, he constructs a new definition of the grotesque and its concomitant vines that displaces it from the grotto and locates it in ornament covering the building’s facade. And yet, by examining the mouth of the head on Santa Maria Formosa, the Venetians, as well as Ruskin, entered a similar passage spiraling downward into the forbidden depths of the mind. Ruskin, like Vitruvius who disparages “slender stalks with heads of men and of animals attached to half the body” – laments that grotesque ornament is the fruit of great minds who “can draw the human head perfectly” yet “cut it off and hang it by the hair at the end of a garland” (11: 170).[42] Despite such protests against the dismembered and hybrid body, the disturbing awareness that a fragmented, rather than whole, body has always lurked within the classical temple contaminates both Ruskin’s and Vitruvius’s treatises.[43] When this ornament begins to show its teeth or to overflow beyond its tolerated cavity as a libidinous body drunk from grapevines that choke the edifice, when it is too full to be contained and bursts forth in unrestrained fecundity, then the cracks of architecture dilate and the grotesque presents its brown and bloody head in an originary moment no longer stable, clean, or progressive.

Notes

1. Vitruvius On Architecture, trans. Frank Granger (New York: Putnam, 1934), 105. On the style of painting Vitruvius describes, see Frances K. Barasch, The Grotesque: A Study in Meanings (The Hague: Mouton, 1971). Barasch explains the terminology of Pompeiian wall paintings: “The Ornate style, which Vitruvius condemned, preceded the fantastic style known today as the Grotesque, the Fantastic, or the Intricate Style. Until the nineteenth century, both Augustan and Titus fantastic styles were regarded as one. Eighteenth-and nineteenth-century restorations at Pompeii and Herculaneum and certain remarks in Vitruvius enabled August Mau and others to identify four stages in the ancient art of Rome as well as Pompeii: 1) The Incrustation Style, c. second century B.C.; 2) The Architectural Style, c. first century B.C.; 3) The Ornate Style (‘Landscape Style’ in Granger’s translation of Vitruvius), which overlapped the second mid-Augustan period to A.D. 63; this was Vitruvius’ period; 4) The Fantastic or Intricate Style, A.D. 63-79.” Cf. Eugenie Strong, Art in Ancient Rome (New York, 1899). Nineteenth-century art historians Alfred Woltmann and Karl Woermann favor the term grotesque for the third style: “Most… of the painting of Herculaneum and Pompeii exhibit… the later grotesque style with which Vitruvius finds fault so bitterly” (quoted in Barasch, The Grotesque, 29).

2. Suetonius, History of the Twelve Caesars, trans. Philemon Holland (1606; reprint, New York: AMS Press, 1967), 2: 124-25.

3. Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, trans. Gaston du C. de Vere, 10 vols. (London: Philip Lee Warner, 1912-15), 8: 75.

4. As cited by Ewa Kuryluk, Salome and Judas in the Cave of Sex: The Grotesque: Origins, Iconography, Techniques (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1987), 105. Also see John Serle, A Plan of Mr. Pope’s Garden (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982). On Pope’s grotto as an optical device, see Jurgis Baltrusaitis, Aberrations: An Essay on the Legend of Forms, trans. Richard Miller (Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1989). Kuryluk cites another description of Pope’s grotto by “an observer from Newcastle”: “To multiply this Diversity, and still more increase the Delight, Mr. Pope’s poetick Genius has introduced a kind of Machinery, which performs the same Part in the Grotto that supernal Powers and incorporeal Beings act in the heroick Species of Poetry: This is effected by disposing Plates of Looking glass in the obscure Parts of the Roof and Sides of the Cave, where a sufficient Force of Light is wanting to discover the Deception, while the other Parts, the Rills, Fountains, Flints, Pebbles, &c. being duly illuminated, are so reflected by the various posited Mirrors, as, without exposing the Cause, every Object is multiplied, and its Position represented in a surprising Diversity. Cast your Eyes upward, and you half shudder to see Cataracts of Water Precipitating over your head, from impending Stones and Rocks, while salient Spouts rise in rapid Streams at your Feet: Around, you are equally surprised with flowing Rivulets and rolling Waters, that rush over airey Precipices, and break amongst Heaps of ideal Flints and Spar.

Thus, by a fine Taste and happy Management of Nature, you are presented with an indistinguishable Mixture of Realities and Imagery” (105-6).

5. Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Winckelmann: Writings on Art, ed. David Irwin (London: Phaidon, 1972), 84-85.

6. The Works of John Ruskin, ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, 39 vols. (London: George Allen, 1904), 11: 161-62. Subsequent references in the text to Ruskin’s writings will be to the volume and page numbers of the Library Edition.

7. Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His WorM, trans. Helene Iswolsky (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 31-32. Bakhtin continues: “What is the character of these ornaments? They impressed the connoisseurs by the extremely fanciful, free, and playful treatment of plant, animal, and human forms. These forms seemed to be interwoven as if giving birth to each other. The borderlines that divide the kingdoms of nature in the usual picture of the world were boldly infringed. Neither was there the usual static presentation of reality. There was no longer the movement of finished forms, vegetable or animal, in a finished stable world; instead the inner movement of being itself was expressed in the passing of one form into the other, in the ever incompleted character of being. This ornamental interplay revealed an extreme lightness and freedom of artistic fantasy, a gay, almost laughing, libertinage. The gay tone of the new ornament was grasped and brilliantly rendered by Raphael and his pupils in their grotesque decoration of the Vatican loggias” (32).

8. Manfredo Tafuri, Theories and History of Architecture, trans. Giorgio Verrecchia (New York: Harper and Row, 1980), 17.

9. Mark Taylor, “Nuclear Architecture or Fabulous Architecture or Tragic Architecture or Dionysian Architecture or…,” Assemblage 11 (April 1990): 14. Taylor applies his theory of the grotesque architectural body to the work of Peter Eisenman, writing that “Eisenman’s gaping architecture — like all such gaps – is grotesque…. Does this grotesque other have anything to do with a tomb or crypt?” (14).

10. Jennifer Bloomer, Architecture and the Text: The (S)crypts of Joyce and Piranesi (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 49.

11. Vasari, Lives, 5: 229. Vasari also writes: “He was a melancholy person, and was constantly studying the antiquities; and seeing among them sections of vaults and ranges of walls adorned with grotesques, he liked these so much that he never ceased from examining them…. He was never tired, indeed, of examining all that he could find below the ground in Rome in the way of ancient grottoes, with vaults innumerable” (227).

12. On the origins of the grotesque, see also Geoffrey Galt Harpham, On the Grotesque: Strategies of Contradiction in Art and Literature (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 27. Harpham writes: “More because of the setting than because of any qualities inherent in the designs themselves, a consensus soon emerged according to which the designs were called grottesche – of or pertaining to underground caves. Like Vitruvius’s judgment, this naming is a mistake pregnant with truth, for although the designs were never intended to be underground, nor Nero’s palace a grotto, the word is perfect. The Latin form of grotta is probably crupta (cf. ‘crypt’), which in turn derives form the Greek Krupth, a vault; one of the cognates is Krupteig, ‘to hide.’ Grotesque, then, gathers into itself suggestions of the underground, of burial, and of secrecy” (27).

13. By architectural origins I am, in part, invoking Abbe Laugier’s little rustic hut and his dismissal of the cave. Laugier writes: “The savage, in his leafy shelter, does not know how to protect himself from the uncomfortable damp that penetrates everywhere; he creeps into a nearby cave and, finding it dry, he praises himself for his discovery. But soon the darkness and foul air surrounding him make his stay unbearable again” (Marc-Antoine Laugier, An Essay on Architecture, trans. Wolfgang Herrmann [Los Angeles: Hennessey and Ingalls, 1977], 11). On the symbolic relationship between the cave and the female body, Kuryluk writes: “The European symbolism of the cave as a dwelling-place of mythical femininity, personifying fertility and regeneration of earth and water, was established in Greece…. Homer speaks of the elemental architecture created by nature and of life originating from it. His image inspires endless fantasy, as in Porphyrius’s extensive commentary on the cave of naiads in the Odyssey. The length of this mystical text conveys the significance Porphyrius attributed to the grotto as a metaphor for the spirit of the earth and the mysteries of procreation. The luminous gods, incarnations of sunlight and reason, visit the cave, but its permanent inhabitants are the shadow, the unconscious, and the female. Nature is a she and in her subterranean chambers dwell all great goddesses, like Venus and Diana” (Salome and Judas in the Cave of Sex, 100). Kuryluk also explains that “the shell is one of the emblems of the grotesque, not only in architecture but also in the decorative arts. The predilection for it reflects both its inherent qualities and the universal reverie provoked by the miraculous creation of snails, which produce houses of their own substance – as if from nothingness. Being an intimate enclosure, the shell has been regarded as the symbol of the vagina and the uterus; hence it can be viewed as a miniature grotto” (103).

14. Ruskin’s accusation of “drunkenness” alludes to a set of iconographic relationships between grotesque vines and ripe grapes that Stephen Bann, The True Vine: On Visual Representation and the Western Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), outlines beautifully: “Grapes are the origin of one of the most prevalent myths about representation in the West: the story of the Greek painter Zexius, whose skill was so great than even the birds flew down to peck at the deceptive patches of pigment crafted by his brush” (6). He continues: “the motif of the grape vine, in its infinite variety of decorative uses, seems to concretize in a particular way the quality of being ‘present in sensuous abundance.’ This feature can be traced in the painted designs of the Greek and Etruscan pottery of the ancient world, where there is often a precise painterly expression of the exuberance of the vine motif. (Exuberance, we might note, is a word related etymologically to uber, the Latin word meaning ‘abundant.’)” (7). And finally: “The representation of the grape, differentiated from the remaining iconography by its materiality and (almost) its liquidity, suggests an implicit metonymic connection between the container and the contained – between the dots and pools of pigment and the invigorating flow of wine” (8).

15. Samuel Rogers, “Italy,” in The Poetical Works of Rogers, Campbell, J. Montgomery (Philadelphia: J. Grigg, 1836), 51. Rogers devotes a section of this poem to “The Brides of Venice.” The phrases I am quoting come from a passage that reads:

At noon, a distant murmur through the crowd,

Rising and rolling on, announced their coming;

And never from the first was to be seen

Such splendor or such beauty. Two and two

(The richest tapestry unrol’d before them),

First came the Brides in all their loveliness;

Each in her veil, and by two bridemaids follow’d,

Only less lovely, who behind her bore

The precious caskets that within contain’d

The dowry and the presents. On she moved,

her eyes cast down, and holding in her hand

A fan, that gently waved, of ostrich- feathers.

Her veil, transparent as the gossamer,

Fell from beneath a starry diadem;

And on her dazzling neck a jewel shone,

Ruby or diamond or dark amethyst;

A jewell’d chain, in many a winding wreath,

Wreathing her gold brocade.

16. While Ruskin translates casseleri into the building trades, the other possible translation of the word as “casket makers” suggests my mentioning Freud’s essay “The Theme of the Three Caskets” of 1913 (in Sigmund Freud, Collected Papers, ed. and trans. James Strachey, vol. 4 [London: Hogarth Press, 1950]). This story involves a scene from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice in which Portia’s suitor will be determined by his proper selection of a casket containing her portrait. As Freud points out, Shakespeare borrows this story of weddings and chests from a tale in the Gesta Romanorum. Of the three men selecting between three caskets in Shakespeare’s tale, Freud writes: “If we had to do with a dream, it would occur at once to us that caskets are also women, symbols of the essential thing in woman, and therefore of a woman herself, like boxes, large or small, baskets, and so on” (245-56). Referring to the three sisters in King Lear, Freud concludes his analysis of the caskets: “One might say that the three inevitable relations man has with woman are here represented: that with the mother who bears him, with the companion of his bed and board, and with the destroyer. Or it is the three forms taken on by the figure of the mother as life proceeds: the mother herself, the beloved who is chosen after her pattern, and finally the Mother Earth who receives him again” (256).

17. Edward Muir, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), 135. As Muir clarifies, this legend, or fabrication, explained a preexisting ritual: “In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries it was generally believed that the annual ceremonies at the church of Santa Maria Formosa had begun in the tenth century as a celebration of a victory over pirates. An anonymous chronicle composed at the end of the fifteenth century, perhaps the most detailed account of the legend, claims that since ‘ancient times’ on January 31, the day of the transfer of Saint Mark, the prince and commune gave dowries to and sponsored weddings for twelve deserving but poor young girls in a ceremony conducted by the Bishop at his cathedral of San Pietro di Castello. One year a group of Triestine pirates, tempted by the girls, their dowries, and the gems with which the prince adorned them for the occasion, stole their way into the cathedral; after attacking and wounding or killing many of the assembled worshippers, the pirates fled the cathedral with the bejeweled brides and their dowry boxes, escaping aboard boats they had hidden outside. Quickly assembling a fleet, the Venetian men folk pursued them to a small port near Caorle – to this day called the Porto delle Donzelle – where the Triestines had anchored to divide the spoils. First to board the pirate craft, the casseleri (either cabinetmakers or carpenters) of the parish of Santa Maria Formosa fought valiantly, killed all the Triestines, threw the corpses without ceremony into the sea, and burned the ships. Returning with brides, dowries, and treasures intact, the casseleri won honors for the victory, which occurred on February 2, the day of the Purification of the Virgin, or Candlemas. To reward the casseleri the doge agreed that he and his successors would visit Santa Maria Formosa each year following vespers on the eve of the Purification and for mass of the feast day itself” (135-56).

18. Ibid., 137.

19. Ibid., 140. Also see Tony Tanner, Venice Desired (Oxford: Blackwell, 1992). As Tanner observes, “a fiercely intransigent Protestant at the time, Ruskin was constantly having trouble with the Mariolatry (indeed the female altogether) and more generally the undeniable fact that it was Catholicism which had inspired or informed much of the art and architecture he most admired (while Protestantism seemed to nourish little or none)” (94). Given this bias, Muir’s observations regarding the cult of Mary in Venice will help to account for Ruskin’s position regarding Santa Maria Formosa. Muir explains that “the Venetians, indeed, assiduously venerated the Virgin Mary. Her cult was so popular and so ancient that, like many other cities, Venice was often identified as the city of the Virgin.” He also writes that “the Festival of the Marys paraphrased the peculiar status of women in trecento Venetian society. In two recent articles Stanley Chojnacki has shown that women, especially patrician ladies, had a distinctive and important social and economic influence that contributed to the harmony and stability of Venetian society. In a patrician regime such as that of Venice, a complex of attitudes, legal precepts, and rules of inheritance served to protect the patriline as the foundation of society. In Venice a woman had a ‘curious status’: she was exiled from the pattiline when she received her dowry – in theory her share of the patrimony – so that the absence of an obligatory orientation toward her paternal kin permitted her to mediate between two patrilines allied through her in marriage. Thus, women contributed, in particular, to the strength and stability of the patriciate by bonding together various patrician lineages. Moreover, through their ability to make bequests, dispose of their own dowries in their wills, and invest independently in business, women were able to exert psychological pressure on their male kin and to express personal preferences without regard to lineage” (Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice, 15051).

20. In the entry on the Ospadeletto Church in the “Index” to The Stones, Ruskin writes: “The most monstrous example of the Grotesque Renaissance which there is in Venice; the sculptures on its facade representing masses of diseased figures and swollen fruit. It is almost worth devoting an hour to the successive examination of five buildings, as illustrative of the last degradation of the Renaissance. S. Moist is the most clumsy, S. Maria Zobenigo the most impious, S. Eustachio the most ridiculous, the Ospadeletto the most monstrous, and the head at S. Maria Formosa the most foul” (11: 397). Also see Arnold Whittick, ed., Ruskin’s Venice (London: George Godwin, 1976), 195-56.

21. In volume two, “The Sea Stories,” chapter six, “The Nature of Gothic,” of The Stones, Ruskin offers a hierarchy for the “characteristic or moral elements” of the Gothic building as: 1. savageness, 2. changefulness, 3. naturalism, 4. grotesqueness, 5. rigidity, and 6. redundancy (11: 79), To this he adds the qualities of the Gothic builder: 1. savageness or rudeness, 2. love of change, 3. love of nature, 4. disturbed imagination, 5. obstinacy, and 6. generosity. Thus the grotesque and a disturbed imagination are aligned. While he carefully explains what he means by each of these separate characteristics, when he arrives at the grotesque he writes: “The fourth essential element of the Gothic mind was above stated to be the sense of the GROTESQUE; but I shall endeavor to define this most curious and subtle character until we have occasion to examine one of the divisions of the Renaissance schools, which was morbidly influenced by it. It is the less necessary to insist upon it, here, because every reader familiar with Gothic architecture must understand what I mean, and will, I believe, have no hesitation in admitting that the tendency to delight in the fantastic and ludicrous, as well as in sublime, images, is a universal instinct of the Gothic imagination” (11: 203). It is important to note that Ruskin is attracted to the grotesque of the Gothic period: “There is iest — perpetual, careless, and not infrequently obscene –in the most noble work of the Gothic periods; and it becomes, therefore, of the greatest possible importance to examine into the nature and essence of the Grotesque itself, and to ascertain in what respect it is that the jesting of art in its highest flight, differs from its jesting in its utmost degradation” (11:113). Also see Barbara Maria Stafford, “’Illiterate Monuments’: The Ruin as Dialectic of Broken Classic,” The Age of Johnson. Stafford observes, “Especially noteworthy is Ruskin’s construct of the natural grotesque which for him is close to a total, comprehensive art capable of bringing into conjunction the multiple oppositions of the world: the one with the many, the divine with the monstrous” ( 3).

22. Similarly, on Ruskin’s relationship with Venice, Tanner writes in Venice Desired: “In Venice with his young wife, Effie, their marriage unconsummated, his abstinence could hardly be further from Byron’s dissipation. Whereas Effie enjoyed the available social life, Ruskin preferred to avoid it and attended on sufferance, suffering. His business was with those under-canal vaults and mud-buried porticoes. I might have said his assignation -for Ruskin seems to have literally crawled and climbed over the whole ruined body of a city; peering with his incomparable eye into every darkened nook and cranny, high and low; gently picking over the abandoned stones of decaying palaces; gliding into and down the darkest and dingiest canals. It would be too easy and not particularly illuminating to talk of a massive displacement of the activities of the marriage bed into the exploration of the city. But, if the word means anything at all, there can be no doubt that Ruskin’s most intense love-affair was with Venice, and his writings about her from the first to last manifest, at their extreme, the positive and negative efflorescences of the unresting desire which the very idea, image, memory of the city aroused in him” (68-69).

23. Ibid., 72, 81.

24. Bann, The True Vine, 28, 39.

25. Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay in Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 40. Kristeva develops this concept when describing a little girl, frightened of being eaten up by a dog, who spoke more intensely the more frightened she became. Kristeva writes: “Through the mouth that I fill with words instead of my mother whom I miss from now on more than ever, I elaborate that want, and the agressivity that accompanies it by saying. It turns out that, under the circumstances, oral activity, which produces that linguistic signifier, coincides with the theme of devouring, which the ‘dog’ metaphor has a first claim on. But one is rightfully led to suppose that any verbalizing activity, whether or not it names a phobic object related to orality, is an attempt to introject the incorporated items. In that sense, verbalization has always been confronted with the ‘object’ that the phobic object is” (41). With the grotesque we find a devouring architecture – what Pirro Ligofio refers to as la insatiabilita – an architecture that can consume itself. Regarding this specific reference and the Renaissance understanding of the grotesque, see David Summers, Michelangelo and the Language of Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981). Summers’s research indicates that the cinquecento attitude toward the grotesque was by no means uniform; he discusses the writings of Ligorio, Sebastiano Serlio, and G. P. Lomazzo on this subject: “Grotteschi are made ‘to bring amazement and marvel (stupore et maraviglia) to miserable mortals, to signify as much as may be possible the pregnancy and fullness of the intellect and its meanings… to accommodate the insatiability (la insatiabilita) of the various and strange concetti drawn from the so great variety that is created in things.’ At the same time, those ‘moderns’ misunderstand such paintings, who call them merely ‘grottesche et insogni et stravaganti pitture anzi mostruose.’ He argues that they do and should conceal mysteries; this attempt to give grotteschi an allegorical significance is at base an attempt to subject them to decorum. Ligorio generally rejects the kind of free and fantastic construction for which grotteschi stood; for him, they are not audaciae, but rather a mode of symbolic thought…. Ligorio almost always writes of Michelangelo himself with respect, but like Vasari in the second edition, he heaps coals on the heads of his followers, the Michelagnolastri whose license in both painting and architecture he abhors. Ligorio’s attitudes toward grotteschi and toward the question of invention in general were, in short (at least at the time he wrote) precisely parallel. The question of the relation of pure ornamental invention to the invention or allegory deserves careful separate attention. In his discussion ofgrotteschi, Serlio… stressed freedom of invention within definite architectural frameworks. Lomazzo… stresses in addition the possibilities for significance of such inventions, calling them ‘enigmas, or ciphers, or Egyptian figures, called hieroglyphics, to signify some concerto or pensiero under another form (sotto altre figure), as we do in emblems and imprese’; grotteschi are most suitable to the expression of all meaning because they include ‘tutto quello che si trovare et imaginare”’ (496-67).

26. Harpham, On the Grotesque, 31.

27. Immanuel Kant, The Critique of Judgment, trans. James Creed Meredith (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), 173. While the subject of the grotesque in relation to the sublime is beyond the scope and intention of this essay, I will offer one or two observations on this subject that will help to place Ruskin in this larger theoretical context. Ruskin specifically refers to the sublime in his analysis of the grotesque as a distinct aesthetic category: “The reader is always to keep in mind that if the objects of horror, in which the terrible grotesque finds its materials, were contemplated in their true light, and with the entire energy of the soul, they would cease to be grotesque, and become altogether sublime” (11: 178). He also writes: “Now, so far as the truth is seen by the imagination in its wholeness and quietness, the vision is sublime; but so far as it is narrowed and broken by the inconsistencies of the human capacity, it becomes grotesque” (11: 181). Similarly, Victor Hugo, in Dramas: Oliver Cromwell (Philadelphia: George Barrie and Son, 1896), discusses the close proximity between the grotesque and the sublime: “the ugly exists beside the beautiful, the misshapen beside the graceful, the grotesque beside the sublime, evil with good, darkness with light”

(25). But, unlike Ruskin, Hugo sees this as a necessary and inherent relationship: “modern genius springs from the fruitful union of the grotesque type and the sublime” (27). For Hugo, the grotesque serves “as a glass through which to examine the sublime, as a means of contrast, the grotesque is in our judgment, the richest source of inspiration that nature can throw open to art” (32). See also Suzanne Guerlac, The Impersonal Sublime: Hugo, Baudelaire, Lautreamont (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990). It is, of course, with Kant that the grotesque/sublime receives its philosophical elaboration. As Kant writes in The Critique of Judgment, the sublime is “a feeling of displeasure, arising from the inadequacy of the imagination in the aesthetic estimation of magnitude to attain to its estimation by reason, and a simultaneously awakened pleasure, arising from this very judgment of the inadequacy of the greatest faculty of sense being in accord with ideas of reason, so far as the effort to attain these is for us a law” (106). This pleasure involves the mind set in motion versus the mind set in restful contemplation, a movement comparable to “a vibration, i.e., with a rapidly alternating repulsion and attraction, produced by one and the same Object” (107). Apropos of Ruskin, Kant discusses the sensation of sublime fear: “we may look on an object as fearful, and yet not be afraid of it” because “one who is in a state of fear can no more play the part of a judge in the sublime of nature than one captivated by inclination and appetite can of the beautiful” (110). As with Ruskin, who will distinguish between the noble and ignoble grotesque in terms of the interested and the apathetic artisan, Kant writes: “Every affection of the STRENUOUS TYPE (such, that is, as excites the consciousness of our power of overcoming every resistance [animus strenuus]) is aesthetically sublime, e.g., anger, even desperation (the rage of forlorn hope but not faint-hearted despair). On the other hand, affection of the LANGUID TYPE (which converts the very effort of resistance into an object of displeasure [animus languidus]) has nothing noble about it, though it may take its rank as possessing beauty of the sensuous order” (125). Pertinent to Ruskin’s sermonizing, Kant invokes the primary crisis of representing the sublime, “perhaps there is no more sublime passage in the Jewish law than the commandment: Thou shall not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven or on earth, or under the earth &c.” (127). Kant explains that this law is based on the fear that we will fail to adequately represent the image and then render it lifeless and cold. Kant specifically mentions the grotesque when writing that “thus English taste in gardens, and fantastic taste in furniture, push the freedom of imagination to the verge of what is grotesque – the idea being that in this divorce from all constraint of rules the precise instance is being afforded where taste can exhibit its perfection in projects of the imagination to the fullest extent” (88). Finally, Kant describes an ornamental motif that fits our earlier descriptions of the grotesque: “So designs a la grecque, foliage for framework or on wall-papers, &c., have no intrinsic meaning; they represent nothing — no Object under a definite concept — and are free beauties. We may also rank in the same class what in music are called fantasias (without a theme), and indeed, all music that is not set to words” (72).

28. Tanner, Venice Desired, also cites this significant passage in The Stones, observing that “Ruskin buries Venice under the Bible, drawing on scriptural wrath and prophecy to inscribe at once its damnation and annihilation” (118).

29. Ruskin takes this line from canto 9 of Dante’s Inferno. The section containing this quotation reads in full: “And more he said, but I have it not in memory, for my eye had wholly drawn me to the high tower with the glowing summit, where all at once three hellish blood-stained Furies had instantly risen up. They had the parts and bearing of women, and they were girt with greenest hydras. For hair they had little serpents and cerastes bound about their savage temples. And he, who well recognized the handmaids of the queen of eternal lamentation, said to me, ‘See the fierce Erinyes! That is Megaera on the left; she that wails on the right is Alecto; Tisiphoe is in the middle’; and with that he was silent. Each was tearing at her breast with her nails; and they were beating themselves with their hands, and crying out so loudly that in fear I pressed close to the poet. ‘Let Medusa come and we’ll turn him to stone,’ they all cried, looking downward. ‘Poorly did we avenge the assault of Theseus.’ ‘Turn your back, and keep your eyes shut; for should the Gorgon show herself and you see her, there would be no returning above.’ Thus said the master, and he himself turned me round and, not trusting to my hands, covered my face with his own hands as well. O you who have sound understanding, mark the doctrine that is hidden under the veil of the strange verses! And now there came over the turbid waves a crash of fearful sound, at which both shores trembled: a sound as of a wind, violent from conflicting heats, which strikes the forest and with unchecked course shatters the branches, beats them down and sweeps them away, haughtily driving onward in its cloud of dust and putting wild beasts and shepherds to flight” (Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, trans. Charles Singleton, vol. 1 [Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970], 90-93).

30. Sigmund Freud, “Medusa’s Head” (1922), in Collected Papers, vol. 5 (London: Hogarth Press, 1952), 105.

31. Ibid., 106. On the 1848 revolution, see Neil Hertz, “Medusa’s Head: Male Hysteria Under Political Pressure,” in The End of the Line: Essays on Psychoanalysis and the Sublime (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985).

32. Ann Bergren, “Baubo and Helen: Gender in the Irreparable Wound,” in Drawing, Building, Text: Essays in Architectural Theory, ed. Andrea Kahn (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1991), 110.

33. In a footnote to this paragraph, Ruskin adds: “This opposition of art to inspiration is long and gracefully dwelt upon by Plato, in his ‘Phaedrus’; using, in the course of his argument, almost the words of St. Paul:… ‘It is the testimony of the ancients that the madness which is of God is a nobler thing than the wisdom which is of men,” and again, ‘He who sets himself to any work with which the Muses have to do,… without madness, thinking that by art alone he can do his work sufficiently, will be found vain and incapable, and the work of temperance and rationalism will be thrust aside and obscured by that of inspiration.’”

34. Jean-Martin Charcot and Paul Richer, Les Difformes et les malades dans l’art (1889; reprint, Amsterdam: B. M. Israel, 1972) 1: “Une tete enorme, inhumaine et monstrueuse, ditil, ricanante, d’une espression qui la ravale au niveau de la brute, trop abjecte pour etre representee ou decrite, et qu’on ne saurait contempler au dela de quelques instants…. On peut y voit l’indice de cette complaisance a contempler la degradation de la brute et l’expression du sarcasm bestial, qui est, je crois, l’etat d’esprit le plus deplorable ou l’homme puisse descendre.”

35. Georges Didi-Huberman, “Charcot, l’histoire et l’art: Imitation de la croix et demon de l’imitation,” in Jean-Martin Charcot and Paul Richer, Les Demoniaques dans l’art (1887; reprint, Paris: Macula,1984), 169. Translation from the French by Jeffrey Balmer.

36. Charcot, Les Demoniaques, 24 (my emphasis). Debora Silverman’s article on Charcot’s “hallucinatory interior” (filled with arabesques), “A Fin de Siecle Interior and the Psyche: The Soul Box of Dr. Jean-Martin Charcot,” Daidalos 28 (June 1988), brought my attention to these comparative images. She writes: “Charcot was particularly fascinated by artistic creativity; he was celebrated by his contemporaries, Sigmund Freud among them, for transposing artistic categories to medicine and for creating a new visual language of diagnosis. His yearnings for an artistic career were pressed into the service of his medical practice…. Charcot invented a new visual language for diagnosis, the ‘clinical-picture method’, which was his greatest contribution as a clinician” (27).

37. See John Dixon Hunt, The Wider Sea: A Life of John Ruskin (London: J. M. Dent, 1982). Hunt explains that the death of Rose La Touche “only intensified, rather than mitigated, Ruskin’s obsession: during the winter of 1876-77 his study of Carpaccio’s St. Ursula cycle became so entwined with his thought of Rose that the virgin-martyr and the Irish girl merged in his precariously stable mind” (199). Ruskin copied the Dream of St. Ursula that had been put in a special room for his disposal. “The sleeping saint and the ‘sleeping’ Rose La Touche merged fitfully in Ruskin’s mind. The painting seemed so real that he could at times convince himself that it was Rose, simply sleeping” (365). This delusion continued until Rose actually appeared to Ruskin in a miraculous apparition.

38. Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 313. As Bakhtin argues, all the features of the human face are instrumental to the grotesque, “but the most important of all human features is the mouth. It dominates all else. The grotesque face is actually reduced to the gaping mouth; the other features are only a frame encasing this wide-open bodily abyss” (317). He observes that the gaping mouth is related to the lower bodily stratum, it is “the open gate leading downward into the bodily underworld. The gaping mouth is related to the image of swallowing, this most ancient symbol of death and destruction. At the same time, a series of banquet images are also linked to the mouth” (325). And once again, “Birth and death are the gaping jaws of the earth and the mother’s open womb. Further on, gaping human and animal mouths will enter into the picture” (329).

39. In of terms the vaginal orifice and the spoken word, Bakhtin also mentions Denis Diderot’s Les Bijoux indiscrets, a story in which women’s vaginas literally speak of their sexual secrets. The English translation of Diderot’s work, The Indiscreet Jewels, takes us back to the gems adorning the brides, as well as their little boxes, as metonymical references to their anatomy.

40. Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osborne (New York: Verso, 1977), 171. Benjamin is referring to a section in the Natural History where Pliny writes: “On the other hand, ‘A picture by Serapio,’ says Varro, ‘covered the whole of the Maenian Balconies at the place beneath the Old Shops.’ Serapio was a most successful scene-painter, but he could not paint a human being” (Natural History, trans. H. Rackman [Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1912], bk. 35, 113).

41. Also see Barasch, The Grotesque: “By 1524, grottesche became associated with anti-Vitruvianism. The fantastic style was clearly a deviation from classical conceptions of reality, from the perfected forms of the ancients which had their basis in nature, and from the standard of moral and philosophical simplicity by Vitruvius” (30). In comparison to the Vitruvian point of view, Barasch sets up Vasari as his theoretical counterpart: “The Vasarian position, which many of his readers held, was essentially this: The masters of the fourteenth century (the second age of painting) had introduced rule, order, proportion, draughtsmanship, and manner, and in so doing had rendered a great service to the progress of painting, but in the third and greatest age of painters, architects, and sculptors, the artists ‘seeing excavated out of the earth certain antiquities’ were able to attain the perfection of the arts” (31). This perfection consisted of accepting freedom within the rules.

42. Ruskin writes: “If we can draw the human head perfectly, and are masters of its expression and its beauty, we have no business to cut it off, and hang it up by the hair at the end of a garland. If we can draw the human body in the perfection of its grace and movement, we have no business to take away its limbs, and terminate it with a bunch of leaves.”

43. Indeed, without exactly saying so, Vitruvius actually licenses this contamination when he inscribes the well-built male body in a circle and simultaneously extends the anthropomorphic analogy to the orders; he describes an architecture of multiple, ornamental bodies.

Credits:

Source: Assemblage, 1997 Apr., n.32, p.[110]-125, photographs, drawings

Place of Publication: Massachusetts

Abstract: In issue feature on Ruskin

Subject(s): Architecture — Theory — 19th century

Grotesques Relief (Sculpture) — Italy — Venice

Figure Credits

Engravings from Jean-Martin Char-cot and Paul Richer, Les Difformes et les malades dans l’art (1889; reprint, Amsterdam: B. M. Israel, 1972).

Photographs by Paulette Singley.

PHOTO (BLACK & WHITE): The grotesque mask at Santa Maria Formosa and the face of a male hysteric

~~~~~~~~

By Paulette Singley

Paulette Singley is an assistant professor of architecture at Iowa State University and a doctoral candidate in architectural history at Princeton University.

Related Posts :

Category: Article

Views: 17147 Likes: 1

Tags: paulette singley , ruskin , santa maria formosa

Comments:

Info:

Info:

Title: Devouring architecture: Ruskin’s insatiable grotesque

Time: 19 settembre 2013

Category: Article

Views: 17147 Likes: 1

Tags: paulette singley , ruskin , santa maria formosa