Cristiano Toraldo di Francia | Architecture and Rock ‘n’ Roll

interview by Boris Prosperini

When the editors requested me to interview Cristiano Toraldo di Francia, co-founder of SuperStudio, that grayish day turned into a rainbow of psychedelics emotions…my enthusiasm for this item is comparable to the pleasure of a musical critic interviewing the Pink Floyd.

BP: In his article “L’utopia è morta, viva l’utopia” through the history of society into its deepest concepts from the beginning of the century, comparing the research of Superstudio with Archizoom and Archigram. Is, the intrinsic relationship that unites nature and Architecture completely lost today?

CTdF: In the article “L’Utopia è morta, Evvia L’utopia” I concluded by mentioning an intermediate space still active in the last comparison between nature and architecture: the space of “Land-scape- City”. While in China, the land is abandoned to move to increasingly large and extended cities, in the West we are witnessing a return to the land, especially prevalent among young people, disappointed by the third industrial revolution that is eradicating almost all of their base contact with matter, reserved only for migrants fleeing from the south of the planet. It is a continuous flow of populations moving towards the city-regions and of people escaping from the cities toward natural areas and slow temporalities.

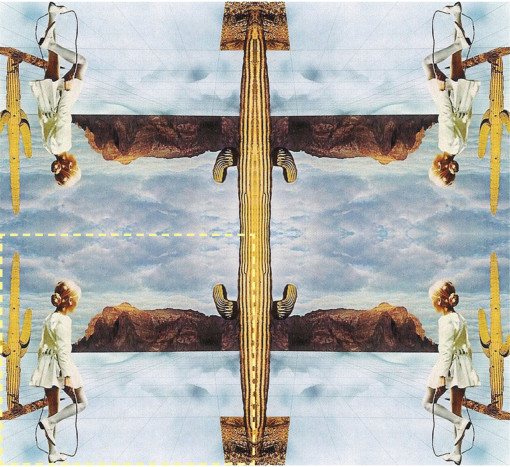

It’s basically what we had foreseen in the depiction of the “Supersuperficie”, as the system of relations and interpersonal communications, are moved to the network, making it an extended place, impalpable and without form, a virtual city-mind, the desire to touch, shape, re-construct and re-connect to the physical world emerges. Who is more afraid of Global tools? Land-Scape-City or rather the slow city is not somewhere else, but only represents a different dimension, a different layer organization of the city-metropolis.

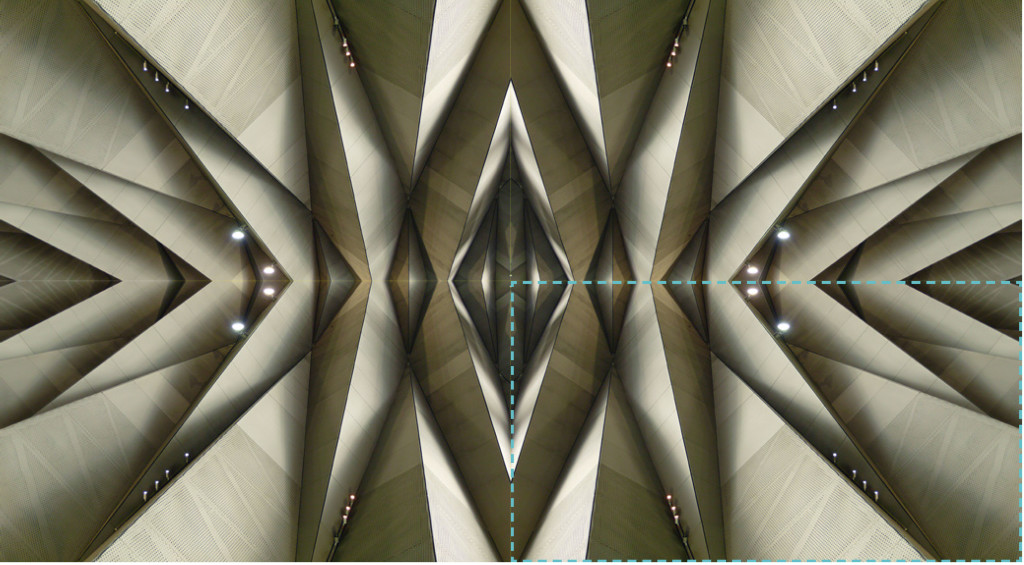

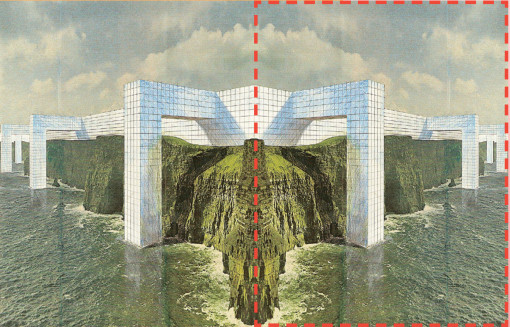

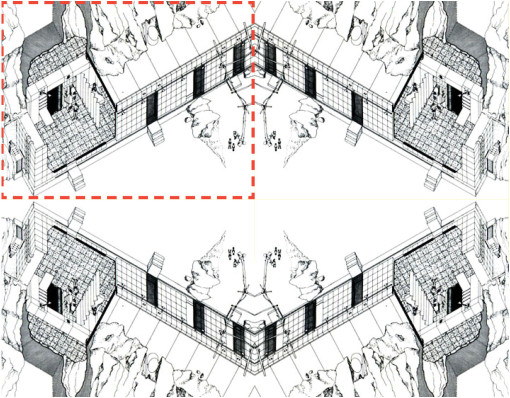

The utopia of the “Ville Radieuse” had sharply distinguished the, mechanics, the level of nature from that of architecture that stood above it bearing on stilts, as indeed happened for the aerial structures of Yona Friedman: two different distinct levels, overlapping but independent. With the Monumento Continuo this ideal division is taken to the extreme, with the first ideal city, we reported a realistic representation of what was happening on a single level: the City was progressively expanding into the countryside, leaving natural archaeological gaps in nature: protected areas.

The rest of the land becomes an agricultural industry, part of the productive functioning of the city, with the exception of those residual or interstitial voids, the third landscape full of biodiversity, or in the process of naturalization, free from instances of new features.

Land-scape-City is therefore a system of spatial relations of the territory, a coplanar and interconnected alternative, but also integrated between nature and architecture. Two systems and two speeds: Slow and Fast with the possibility of continuous osmosis and passages from one layer to another.

The city metropolis in this double natura naturans and naturata, with these continuous changes does nothing but reproduce the flow system in an accelerated and reduced form, which crosses the surface of the planet, from nature to architecture to the industrial metropolis and vice versa, from the latter, into space and slow temporalities.

For example, in the case of the Adriatic City, linear conurbation of 300 km from Ravenna to Ortona along the fast highway A14 and the railway, the new urban configuration could take place not through melting and filling voids, therefore extending the constructions yet again, but through the densification of the existing on the one hand, and through the project of a network of spaces and slow connections on the other: Urbaparco Adriatico.

The shape of the City which is configured within the slow system of parallel Parks of land and sea and of fluvial interconnections, biological corridors and spaces of naturalization, is witnessing a new alliance between nature and architecture.

BP: We talk about the suburbs of large cities. Knowing what has happened in the last half century, where a distorted view, absolutely intentional, of living, generated enormous social differences, institutional dissolution and sentenced its users to a life tainted by a profund ‘apathy’. In which epical way could the suburbs be reviseted, and lead towards a social rebirth?

CTdF: If I had a formula for this epic restyling, maybe I’d be elsewhere, not in an architecture studio, but where these strategies and social policies come to life. I’ve never claimed to have definitive answers, but I’ve always tried to see a possibility of problem finding in architectural design rather than a possibility of problem solving. However, I believe that we should abandon the geographical identification of the periphery as a settlement belt of the city, but to speak of more scattered suburbs, from the dormitory districts, to gated communities, from the outskirts of the shopping centers, to the re-appropriation of abandoned industrial complexes, to the slums, each of which have specific problems, different vitality and social reactions and therefore are subject to different strategies of urban integration.

The urbanistic operation of the Plan already compromised from the outset by the rationalist conception of the division of the city into functional parts, has been further hindered and contradicted, at least in our country, by the overwhelming power of land ownership.

The historical city whose “collage” continued to work until the 900, thanks to close relations between dimensional solids and voids, and its functional overlap, has now exploded into an archipelago of clusters of individual buildings that have separated and made interpersonal relations difficult, related to physical proximity, to which the new neo-disneyan theorists of new urbanism tried to remedy.While I can not agree with Secchi in pointing out the need to “ensure porosity, permeability and accessibility to nature and to the people” through a capillary and isotropic infrastructure that draws attention to the size of the collective, I also see another city arising and is bringing together these scattered parts, which favored the resumption of these relations, exchange of information and political intentions and that are not the result of yet another architectural or urban plan: the network. The network generates the places where 2, 3, 10, 1000 people will find themselves.

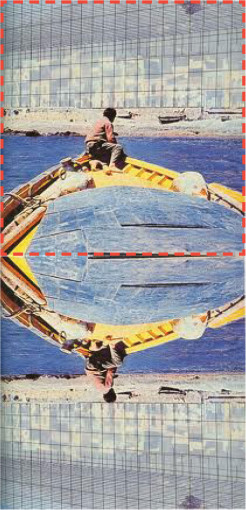

BP: The 1971 “Restauro” project where you imagine to flood the valley of the Arno to find the “state of origin”, where Brunelleschi’s dome was transformed into a huge acing buoy for sailors, is a vision that amazes and shakes me strongly. According to you, returning to the search of extremes can be even that is more useful now, in a society more indifferent and drugged by tools of mass control?

CTdF: In a society that feeds on television programs where you ride the misfortunes of others or where disasters are made show of, in which you can build artificially extreme situations of the dream or nightmare, so as to make them look real and move in space, it is very difficult to find an extreme that still shake the hearts and consciences.

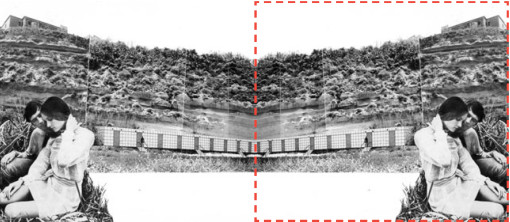

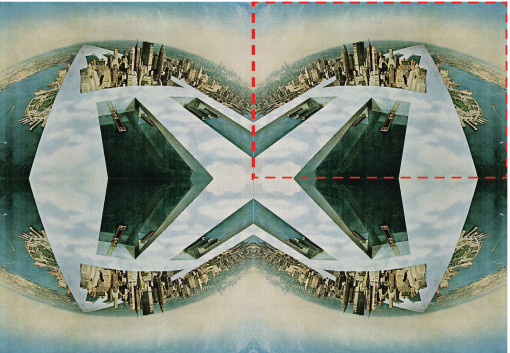

The society of the spectacular generates increasingly driven simulations, fantasies and violence, to attract addicted consumers. Our photomontages, however, were works of handmade crafts, by declaring the two levels of real and hypothetical, we brought them to the limit, but without reaching a perfect simulation, leaving the viewer with doubts about the ambiguous use of the project, the building commission or art gallery, along with the freedom of criticism and rejection.

I therefore still find it essential to have a capacity to imagine that if it is necessary to push a situation to the limits, I’ll do it with extreme realism, such as developments of the contradictions in place and not escape towards the territories of the imagination.

BP: We find ourselves submerged with ‘object’ buildings, where the Vitruvian concepts are no longer known, where the shape coincides with the shape and the same function is uncomfortably connected with the individual. Leading us to forget the history, and resulting in a domestication of the minds, it is a situation that seems impossible to change. What can the effective means to fight this war with the invisible enemy be?

CTdF: Even here you are asking me for solutions that go beyond a simple response to an interview. Stated the fact that most of the built environment, at least in our country, is a trivial building speculation, that little architecture that has been accomplished has had to adapt to the laws of the market, becoming a subject linked to a brand, which is sold independently from the quality of the content.

Given that it is a fact that we got rid of both the tectonic Vetruvian relations, that have come less from the independence between structure and shell, as well as the correspondence between form and function, I do not see how you can prevent a proliferation of formal research at large scale favored by the new computational programs, linked to new technologies and different contexts, as well as, to a lesser scale made of, personal adaptations and transformations of space.

In the moment in which art moves towards the construction of spaces and micro environments, architecture moves towards art to become urban sculpture. Basically, it tries to give back to architecture the role that was of the monuments or icons to communicate with the public at large, outside the narrow circle of specialists, as a test to maintain contact with a world that is in constantly rapid evolution.

BP: In your professional experience along with Adolfo Natalini, you have managed to influence some of the best-known contemporary architects. Who more than anyone else has managed to develop your theories also from a teaching point of view?

CTdF: Among others, the first I think of is Rem Koolhaas who, intrigued by the publication of the Monumento Continuo Domus in ‘68 and by a subsequent lecture by Natalini at AA, where Rem was a young assistant, using our story method for pictures, he developed a discussion about the illusion of utopia and the end of the modern utopia of quality. Inspired by the global dimension of the histogram of the Monumento Continuo, he will arrive at the definition that “big is beautiful”, and at the same time to a description of “generic city”, which also has a precedent in the process of neutrality and generality in both size and formality of the Histograms.

In the early 70s Bernard Tschumi young teacher from AA, took interest in our work from which followed the recognition of the political responsibility of the architect, the idea of dis-junction between space and use, the conviction of the dual nature of conceptual and experiential architecture and thus the confidence in discipline as a tool of knowledge.

Toyo Ito and I confronted each other at a lecture that took place in 2005 at the Nihon University in Tokyo, Ito began his sequence of images starting from the design of Supersuperficie, that is from, the extent of the grid, conceptual image of the architecture of the network, that will then go deforming itself in his plans to adapt to the “blurring” of the vision of society and the liquid nature of space. In a similar lecture /confrontation organized by Piervittorio Aureli (Dogma) in 2007 at the Berlage Institute between myself and Winy Maas (MRDV), entitled “The reality of urban fictions,” Maas preceded each of his projects with an image taken by the photomontages of Superstudio, declaring the debt of gratitude that contemporary Dutch architecture had towards our work and critical methodologies dense of “serious irony,” and the large scale vision of our projects.

BP: Referring to the “Rio de Janeiro” contest organized by CityVision, where visionary projects that are close to utopia are asked for, can you briefly tell us what our ‘68 looks like to you?

CTdF: My ‘68 had already started in 1963 with the occupation of the Faculty of Architecture, it began with the contacts between the student movement and workers’ movement for a common struggle, that would go beyond the logic of trade unions and political parties. We then began to produce designs and images that bypassing the logic of discipline tended to unmask the power relations put in place by the Plan in the construction of the city.

In the explosion of 68 there was, however, the basis for a re-appropriation of the terms of the struggle by the system, ready to blend in like a chameleon with the colors of the predominant context. I45 years later I find myself examining the origin of the projects for Rio de Janeiro,I can acknowledge the global dimension of the critical vision of the architecture of the city that Tafuri had in 1973 with some derision defined as “the international Utopia.“ Once again the tremendous possibilities of architectural design indicate, driving the representations to the limit, the problems of the city and the environment, but also the limited possibility of resolution without the support of appropriate policies on the management of soil properties and the necessary maintenance of the territory.

As usual the network, and also this Cityvision context, are fundamental tools, useful to create a politically planetary conscience that will lead to a sustainable city, providing they distance themselves from specialized magazines and become the new illustrated stories that will be the means for awakening young and old people from a long sleep, creating a new conscience and not only buildings.

ITALIAN VERSION _____________________________________________

B.P. : Nel suo articolo “L’utopia è morta, viva l’utopia!” attraversa la storia della società nei suoi concetti più profondi a partire dall’inizio del secolo breve, comparando la ricerca di Superstudio con Archigram e Archizoom. Oggi la relazione intrinseca che unisce Natura e Architettura è completamente perduta?

CTdF: Nell’articolo “L’utopia è morta, viva l’utopia” concludevo accennando ad uno spazio intermedio che ancora partecipa dell’ultimo confronto tra natura e architettura: lo spazio di “Land-Scape-City”.

Mentre in Cina si abbandona la terra per trasferirsi in città sempre più grandi ed estese, in Occidente si assiste ad un ritorno alla terra, diffuso soprattutto tra i giovani, delusi dalla terza rivoluzione industriale che sta abolendo quasi del tutto il loro contatto di base con la materia, riservato ai soli migranti in fuga dal sud del pianeta. È un flusso continuo di spostamenti di popolazioni verso le città-territorio e di fughe da queste verso spazi naturali e temporalità slow.

È in fondo ciò che avevamo previsto nella raffigurazione della “Supersuperficie”, man mano che si trasferisce sulla rete il sistema delle relazioni e comunicazioni interpersonali, fino a renderlo “luogo” esteso, impalpabile e senza forma, città-mente virtuale, ecco affiorare il desiderio di toccare, plasmare, ri-costruire, di ri-connessione fisica con il pianeta.

Chi ha più paura della Global tools?

LandScape-City ovvero la città slow non è altrove, ma rappresenta soltanto una diversa dimensione, un diverso layer di organizzazione della città-metropoli.

L’utopia della “Ville Radieuse” di LC aveva distinto in maniera netta, meccanica, il livello della natura da quello dell’architettura che la sovrastava poggiata su pilotis; come del resto avveniva per le strutture aeree di Yona Friedman: due differenti distinti livelli sovrapposti, ma indipendenti.

Con il Monumento continuo si porta all’estremo questa ideale divisione, mentre con la prima Città ideale, abbiamo riportato su un unico piano la realistica rappresentazione di quanto stava avvenendo: la Città si espandeva progressivamente nella campagna, lasciando come dei vuoti archeologici di natura: le aree “protette”.

Il resto della campagna diventa industria agricola, parte del funzionamento produttivo della città, ad eccezione di quei vuoti residuali o interstiziali: il terzo paesaggio denso di biodiversità o in via di rinaturalizzazione, libero da istanze di nuove funzionalità.

Land-Scape-City è quindi un sistema di relazioni spaziali del territorio, complanare e interconnesso, alternativo, ma anche integrato tra natura e architettura.

Due sistemi e due velocità: Slow e Fast con possibilità di continue osmosi e passaggi dall’uno all’altro layer.

La città metropoli in questa sua doppia natura naturans e naturata, con questi continui passaggi non fa altro che riprodurre in forma accelerata e ridotta il sistema dei flussi, che attraversano la superficie del pianeta, dalla natura all’architettura verso la metropoli industriale e viceversa da quest’ultima verso spazi e temporalità slow.

Per esempio nel caso della Città Adriatica, conurbazione lineare di 300 km da Ravenna a Ortona lungo la direttrice veloce della autostrada A14 e della Ferrovia, la nuova configurazione urbana potrebbe avvenire non più attraverso la fusione e il riempimento dei vuoti, quindi estendendo ancora una volta il costruito, ma da una parte attraverso la densificazione dell’esistente, dall’altra attraverso il progetto di una rete di spazi e connessioni slow: l’Urbaparco Adriatico.

La forma della Città quale si configura all’interno del sistema slow dei Parchi lineari paralleli di mare e di terra e dalle interconnessioni lungo le Aste fluviali, corridoi biologici e spazi di rinaturalizzazione, è testimone di una nuova alleanza tra natura e architettura.

BP: Parliamo delle Periferie delle grandi città. Conoscendo cosa è successo nell’ultimo mezzo secolo, dove un concetto distorto, assolutamente intenzionale, di abitare, ha generato enormi differenze sociali, dissoluzione istituzionale e condannato i suoi fruitori ad una vita “viziata” da una profonda apatia. In che modo epocale si potrebbero rivisitare le periferie così coinvolgendo la rinascita sociale?

CTdF: Se avessi la formula per questa epocale rivisitazione, forse in questo momento sarei altrove, cioè non negli studi di architettura, ma là dove si mettono in atto strategie politiche e sociali. Non ho mai avuto la pretesa di avere soluzioni definitive, ma ho sempre cercato di vedere nel progetto di architettura più una possibilità di problem finding che di problem solving. Credo comunque che si debba abbandonare la identificazione geografica della periferia come insediamento di cintura della città, ma parlare di più Periferie sparse, dai quartieri dormitorio, alle gated communities, dalle periferie dei centri commerciali, alla riappropriazione di complessi industriali dismessi fino alle baraccopoli e agli slums, ognuna delle quali ha specifiche problematiche, differenti vitalità e reazioni sociali e quindi oggetto di relative differenti strategie di integrazione urbana. Il funzionamento dell’urbanistica del Piano già compromesso in partenza per la concezione razionalista della divisione della città in parti funzionali, è stato ulteriormente ostacolato e contraddetto, almeno nel nostro paese, dallo strapotere della proprietà fondiaria. La città storica il cui “collage” ha continuato a funzionare fino al 900, grazie agli stretti rapporti dimensionali tra i pieni e i vuoti e la relativa sovrapposizione funzionale è oggi esplosa in un arcipelago di agglomerati di singoli edifici che ha separato e reso difficili i rapporti interpersonali, legati alla vicinanza fisica, cui hanno cercato di rimediare i teorici “neo-disneyani” del new urbanesim.

Se da una parte non posso non concordare con Secchi nell’indicare il bisogno di “garantire porosità, permeabilità e accessibilità alla natura e alle persone” attraverso una infrastrutturazione capillare ed isotropa che riporti l’attenzione sulle dimensioni del collettivo, dall’altra vedo che oggi si sovrappone comunque un’altra città che sta riunendo queste parti sparse, che ha favorito la ripresa di questi rapporti, scambi di informazioni e intenzioni politiche e che non è frutto di un ennesimo piano architettonico o urbanistico: la rete. La rete genera i luoghi nei quali ritrovarsi in 2, 3, 10, 1000 persone.

BP: Il progetto del 1971 “restauro” dove immaginavate di inondare la valle dell’Arno per ritrovare lo “stato di origine”, dove la cupola del Brunelleschi si trasformava in una enorme boa di regata per i velisti, è una visione che stupisce e scuote fortemente.

Secondo lei ritornare alla ricerca degli estremi può essere ancor più utile ora, in una società maggiormente indifferente ed narcotizzata attraverso gli strumenti di controllo di massa?

CTdF: In una società che si nutre di programmi televisivi dove si ride delle disgrazie altrui o dove si spettacolarizzano i disastri, e nella quale si possono costruire artificialmente le situazioni estreme del sogno o dell’incubo, sì da farle apparire vere e muovere nello spazio, è ben difficile trovare un estremo che scuota ancora gli animi e le coscienze. La società dello spettacolo genera sempre più spinte simulazioni, fantasie e violenze, per attrarre consumatori assuefatti.

I nostri fotomontaggi invece erano opere di artigianato manuale, che dichiarando i due livelli del reale e dell’ipotetico, li estremizzavano, senza però mai arrivare alla simulazione perfetta, lasciando allo spettatore il dubbio sulla ambigua destinazione del progetto, commissione edilizia o galleria d’arte, insieme alla libertà di critica e rifiuto.

Ritengo quindi essenziale ancora oggi possedere una capacità di immaginazione tale che, se ricorre allo spingere al limite le situazioni, lo faccia con estremo realismo, come sviluppi delle contraddizioni in atto e non fughe verso i territori della fantasia.

BP: Ci ritroviamo sommersi di edifici oggetto, dove i concetti Vitruviani sono oramai cosa sconosciuta, dove la forma coincide con la forma stessa e la funzione è scomodamente connessa con l’individuo. Indurre a dimenticare la storia,con conseguente addomesticamento delle menti, è una situazione che sembra impossibile da cambiare. Quali possono essere i mezzi efficaci per combattere questa guerra con il nemico invisibile?

CTdF: Anche qui mi si chiedono soluzioni che vanno al di là di una semplice risposta ad un intervista. Affermato il fatto che la maggior parte del costruito, per lo meno nel nostro paese, è banale edilizia speculativa, quella poca architettura che si realizza ha dovuto adeguarsi alle leggi di mercato della merce, diventando oggetto legato ad un marchio, che si vende indipendentemente dalla qualità del contenuto. Posto che è un fatto che ci siamo liberati sia dai rapporti tettonici vitruviani, venuti meno dalla indipendenza tra struttura e involucro, così come dalla corrispondenza tra forma e funzione, non vedo come si possa impedire un proliferare di ricerche formali alla grande scala favorite dai nuovi programmi computazionali, legate a nuove tecnologie e diversi contesti, come pure, alla minore scala, personali adattamenti e trasformazioni degli spazi. Nel momento in cui l’arte si sposta verso la costruzione di spazi e di microambienti, l’architettura si sposta verso l’arte per diventare scultura urbana. In fondo si cerca di ridare alle architetture il ruolo che fu dei monumenti, ovvero di icone in grado di comunicare con un pubblico più grande, al di fuori della stretta cerchia degli specialisti, come banco di prova per mantenere il contatto con un mondo in continua rapida evoluzione.

BP: Nella sua esperienza professionale insieme ad Adolfo Natalini, è riuscito ad influenzare tra i più noti architetti contemporanei. Chi più di tutti è riuscito a sviluppare le vostre teorie anche dal punto di vista dell’insegnamento?

CTdF: Penso tra gli altri per primo a Rem Koolhas che, incuriosito dalla pubblicazione su Domus nel ‘68 del Monumento Continuo e da una successiva lecture di Natalini alla AA, dove Rem era giovane assistente, adottando il nostro metodo di racconto per immagini, ha sviluppato il ragionamento intorno alla illusione dell’utopia del moderno e alla fine dell’utopia della qualità.

Ispirato dalla dimensione planetaria dell’istogramma del Monumento Continuo, arriverà alla definizione di “big is beautiful”, contemporaneamente alla descrizione di “generic city”, che ha ugualmente un precedente nel progetto di neutralità e genericità sia dimensionale che formale degli Istogrammi.

Nei primi anni 70 anche Bernard Tschumi giovane docente all’AA, si interessa al nostro lavoro da cui segue il riconoscimento della responsabilità politica dell’architetto, l’idea della dis-giunzione tra spazio e uso, la convinzione della doppia natura concettuale e esperenziale dell’architettura e quindi la fiducia nella disciplina come strumento di conoscenza.

In una lecture confronto tra il sottoscritto e Toyo Ito nel 2005 presso la Nihon University a Tokyo, Ito iniziava la sua sequenza di immagini partendo dal progetto della Supersuperficie, ovvero dalla estensione della griglia, immagine concettuale dell’architettura della rete, che poi si andrà deformando nei suoi progetti per adattarsi al “blurring” di una visione della società e dello spazio di natura liquida.

In una simile lecture confronto organizzata da Piervittorio Aureli (Dogma) nel 2007 presso il Berlage Institute tra il sottoscritto e Winy Maas (MRDV), dal titolo “The reality of urban fictions”, Maas facendo precedere a ogni loro progetto illustrato una immagine tratta dai fotomontaggi di Superstudio, dichiarava il debito di riconoscenza che l’architettura olandese contemporanea doveva al nostro lavoro e alle metodologie critiche dense di “serious irony”, e alla visione a grande scala dei nostri progetti.

BP: Riferendoci al concorso Rio de Janeiro organizzato da CityVision, dove si chiede di narrare progetti visionari, quindi prossimi all’utopia, in breve come le appare il nostro ‘68 ?

CTdF: Il mio 68 era già iniziato nel 1963 con l’occupazione della Facoltà di architettura, quando iniziavano i contatti tra Movimento studentesco e Movimento operaio per una lotta comune autonoma, che si proiettasse oltre le logiche dei sindacati e dei partiti. Iniziammo allora a produrre progetti e immagini che scavalcando le logiche della disciplina tendessero a smascherare i rapporti di potere messi in atto dal Piano nella costruzione della città. Nell’esplosione del 68 c’erano però oramai le premesse per una riappropriazione dei termini della lotta da parte del sistema, pronto a mimetizzarsi come un camaleonte con i colori del contesto predominante. Nell’esaminare 45 anni più tardi di quella data la provenienza dei progetti per Rio de Janeiro, noto la raggiunta dimensione globale di quella visione critica dell’architettura della città che Tafuri aveva nel 1973 definito con una certa derisione come “l’internazionale dell’utopia”. Appare ancora una volta la formidabile possibilità del progetto di architettura di indicare, portandone al limite le rappresentazioni, i problemi della città e dell’ambiente, ma dall’altra la scarsa possibilità di risoluzione senza il supporto di adeguate politiche sulla gestione della proprietà dei suoli e della necessaria manutenzione del territorio.

Come al solito la rete e quindi anche questo concorso di Cityvision sono strumenti fondamentali per generare una coscienza politica planetaria verso la città socialmente “sostenibile”, a patto che escano dalle ristrette cerchie delle riviste specializzate e divengano le nuove “storie” illustrate per una diffusione capillare a risvegliare l’attenzione di ancora troppi, vecchi e giovani, dal grande sonno e costruire non solo edifici ma coscienze.

C.Toraldo di Francia

27.08.2013

www.cristianotoraldodifrancia.it

Related Posts :

Category: Article

Views: 4880 Likes: 7

Tags: boris prosperini , cristianotoraldo di francia , monumento continuo , Superstudio

Comments:

Info:

Info:

Title: Cristiano Toraldo di Francia | Architecture and Rock ‘n’ Roll

Time: 20 settembre 2013

Category: Article

Views: 4880 Likes: 7

Tags: boris prosperini , cristianotoraldo di francia , monumento continuo , Superstudio