AD ASTRA

“Ornament is crime.”

The definitive statement by Adolf Loos in 1908 marked the beginning of European Rationalism and set the trend for cities to shine like white walls, their sole adornment being a sparkling geometric quality. Because of his austerity, Loos is Massimo Cacciari’s angel. The architect of the future is able to compose the dissonance between “space” and “place.” The former is the space that the architectonic project wants to conquer, the tabula rasa of the white wall of a universal city that always expands beyond its borders. The latter is that portion of space that mankind always tries to cut out of the world to make his own, that hidden place where we recognize ourselves as dwellers. Loos succeeded in producing hope and harmony by emphasizing the contrast between the rigid exterior and the fluid, functional interior. An example of this is his Chicago Tribune skyscraper.

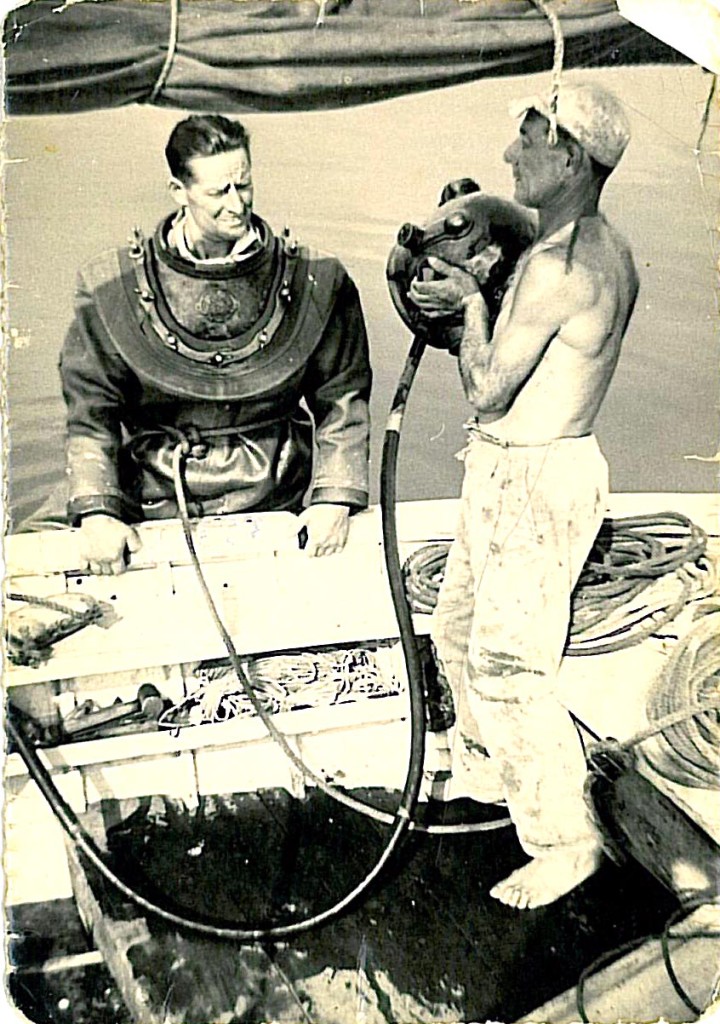

The miraculous balance achieved in Loos’ architecture will be the starting point of Cacciari’s reflections on man, as shown in Abitare, pensare (Dwelling, thinking.) We live on the threshold: pouring into the streets, we are citizens of the world, but we always try to come back home. Is

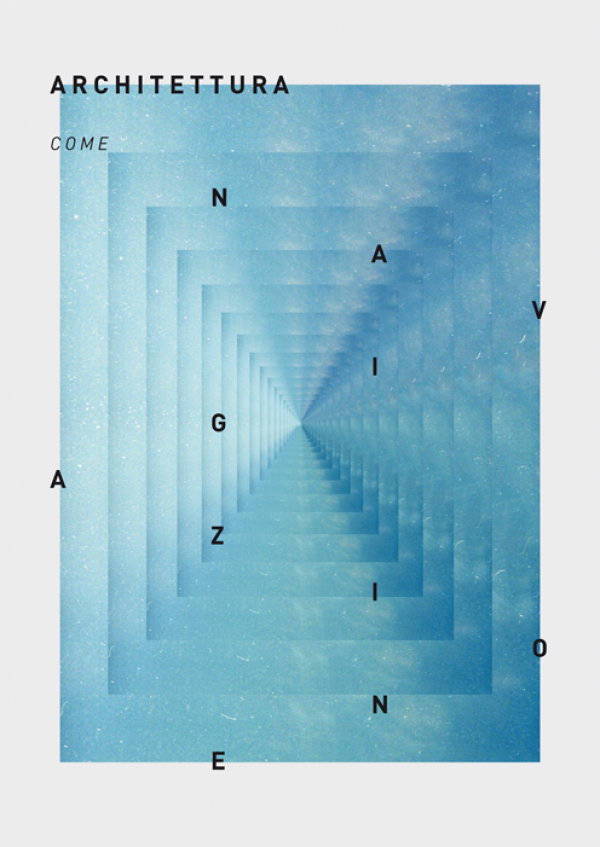

it possible to live in the Open? Can we feel safe in the absence of walls? Passagenwerke, a working passage space, doors that let us cross the city borders, harbours that we can sail from, travelling as fast as information does, we are in perpetual tension between infinity and returning. Stellar wanderers, or members of an earthly fleet that dream of dwelling on the Enterprise.

The architect is Eros, love, because he is the one who keeps on reimagining the house of the future for us. If it is true that we live in a world where we are all just passers by, the house we truly need is one in the form of a boat, a perfect journey in an essential form, floating without the need for foundations, guided by the stars.

text by Marta Benvenuto

illustration “Architettura come navigazione” by Freddy Ventriglia