21ST-CENTURY ARCHITECTURE: The desertion of ethos and the promotion of irrationality?

by Zaheer Allam

As a buoyant and new graduate from high school, and relieved to have left the pedantic world of high school behind, I was brimming with enthusiasm when I finally attended university to join the other avid learners of architecture. Architecture, to me, is poetry in motion and from any problem, emerged an assemblage of shapes that are discrete entities in themselves and yet intricately linked. The set up of the architectural academic syllabus invites interest and arouses curiosity. It is a skilful blend of the basic scientific principles of the subject and its technicalities, the intrigue behind the history of its evolution as well as exploring other modules such as urban design, structure and other such relevant ones. One particular lecture that was imparted in our history class is vividly imprinted on my mind. In that class, we were taught the when and how of the various contributions of architecture to our society in the past century. Much emphasis was placed on how all those additions to the world of design by the famous Bauhaus school, directly or indirectly set in motion numerous changes that ultimately provided a better lifestyle. Thus was born the tenet that architecture had power to change the world and from there on, we considered and prided ourselves on being enlightened.

However, despite our knowledge, when we are asked to produce forth a design, we generally tend to belie those very principles to which we were first introduced. There is a tendency to forget that architecture, in its very essence, has the simple task of providing the solution to a number of problems while not only taking into account the penultimate objectives of the projects but also in analyzing its effects on society. Instead, the goal of our focus and our approach similarly changed to follow a trend that originated in the 19th century which advocates our aim as addressing the issues of our current century. That trend is undoubtedly admirable and suits the needs of the people but due to its rigid timeframe, overlooks the simple fact that society is progress in motion. As our world changes, so do our needs. Architecture, in itself, being an advocate promoting innovation and creativity should reflect that model of change and provide not only for the present but prepare for the future. The words of Juhani (1994, 74) embody the current permeating lack of foresight:”The view of the world and the mission of architecture that had appeared unquestionably grounded in concepts of truth and ethics, as well as in a social vision and commitment, have shattered, and the sense of purpose and order has faded away.”

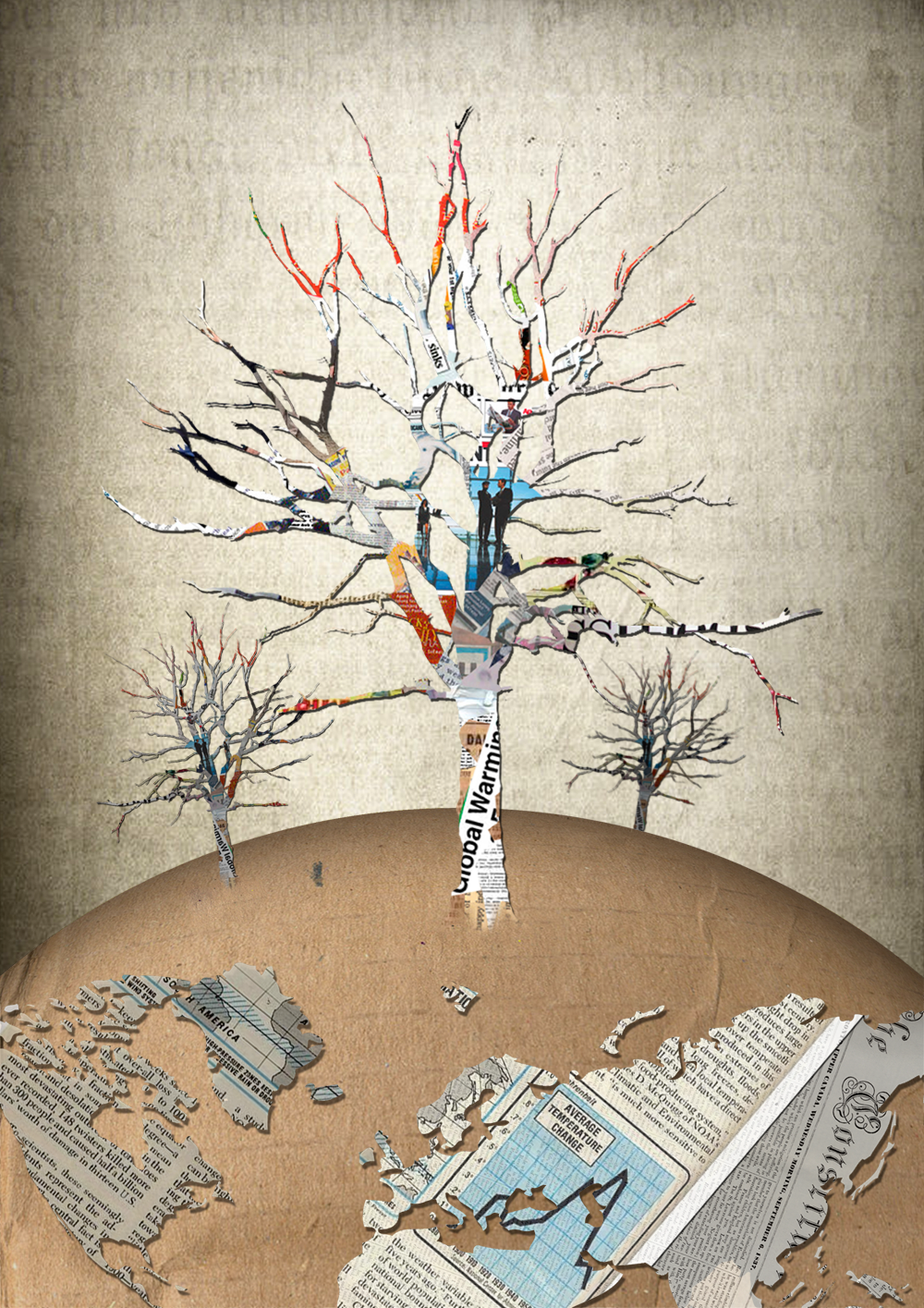

Should we adapt a more flexible frame of vision and widen our scope from the aesthetics aspect that comes with the job to encompass society and the problems that our world is facing on a global scale, we would be aware of the many challenges that are being experienced but that we have yet to concretely address. For an architect, the environment can be an ally or an obstacle to a project. Our relationship is symbiotic and is central to the very foundation of our job. And yet, we have failed to take good notice of the changes affecting our environment. Most places are experiencing extreme climatic changes, sea levels are rising, weather patterns are fluctuating, ecosystems are being stressed, just to mention a few. This phenomenon is the direct effect of global warming. Unfortunately, despite the continuous efforts of scientists and politicians to raise awareness on the matter, people are still either in blissful ignorance or frankly skeptic. But as Barack Obama so rightly said, “Not only is it real, it’s here, and its effects are giving rise to a frighteningly new global phenomenon: the man-made natural disaster.” However, the tragedy of the matter is that this is not a once-off phenomenon. It is a progressive and slow destruction that can culminate in disaster. NASA released a statement delineating that “Scientists have high confidence that global temperatures will continue to rise for decades to come, largely due to greenhouse gasses produced by human activities.”, (Climate change: Effects n.d. ). As designers, we can shoulder a burden of responsibility in attempting to improve the situation through means that take into account potential future changes.

The importance of this issue cannot be emphasized enough. That architects, as much as environmentalists and engineers, have shared responsibility towards sustainable ecology as well “As the construction sector is responsible for an estimated figure of 30-40% of a large part of the total global emissions of climate gases either relating to operational emissions or those related to production, maintenance and demolition.” (Berge 2009, 32). Our focus should be directed towards redefining the concept of building as a whole to encompass every minute detail of the construction process. The erection of the building façade or the energy consumed should not be our sole targets for improvement and change since “Impacts related to the production of materials correspond closely to the embodied energy in the materials though chemical emissions from the products can also play a role.” (Berge 2009, 32).

There are more compelling reasons advocating present action as opposed to inaction where global warming is concerned. Al Gore says,” The warnings about global warming have been extremely clear for a long time. We are facing a global climate crisis. It is deepening. We are entering a period of consequences.” Such consequences would directly impact on our ecosystem but do not define the sole imperative to act now. If we, as architects, do not fulfill a self-obligation to take immediate action to redefine our contribution towards environmental preservation, we will be placing ourselves in a position where it will be too late to find adequate solutions to current problems. More importantly, we will not be able to prevent the advent of larger and more catastrophic changes. We will find ourselves dragged down in a landslide of ecological disasters that will be in part, of our own making.

The irony of the situation is that, while most people spend their time in buildings, relatively little attention is being paid to the built environment. Our designing principles have been put in place to address the need for shelter while also incorporating the creature comforts of living. In doing so, we have flagrantly ignored a critical component of design and that is the interaction of our designs with nature and its impact on it. While various developments contribute to the destruction of vast and diverse ecosystem and bionic communities, we, unknowingly, often attribute the “green label” to those buildings in that area, merely due to the fact that they are either located in greener surroundings as opposed to cities or because they are energy efficient. Let’s not however forget that the concept of energy efficiency is more of a business model than an ecological one. In essence the building structure remains more or less the same, an amalgam of steel and cement encased in materials rich in embodied energy that contribute to the release of CO2 in our atmosphere.

This validates the urgent need for the search of resources that are already in existence or the development of materials that have less of a negative impact on our ecosystems. One example of readily available materials is earth, clay and straw. These have been used as basic tools since the B.C era due to their properties of having strong resistance and yet displaying flexibility, which makes them more advantageous than concrete and rebar. One might argue than earthen construction does not boast the same aesthetic outlook than a concrete façade. This is undoubtedly due to the fact that comparison is being made to earthen structures that were built centuries ago. With modern construction techniques, a façade made of rammed earth can look as good and linear as one made of concrete. While engineering prowess works towards reinforcing the structural integrity of common materials of construction, we, as architects, should focus on discovering new ways to work with the byproducts of nature and use them to both our and the earth’s benefit.

What is more is that architecture is still shrouded in mystery and most people still find it an abstract concept. This lack of an intelligent and understanding relationship between people and architecture has been present for far too long and unfortunately makes up the terrain on which architects maneuver. In an era where rational thought was inexistent, this would have been an acceptable premise. However, in this modern day and age, when the human mind has transcended all limits, it is illogical that architecture continues to be perceived in a semi-mystical fashion. (Saligaros and Masden II 2007, 46).

This permeating lack of understanding leads to the design of building envelopes of all kinds, which, sadly, are interpreted as being of artistic or creative nature. Once that label is ingrained to particular buildings, it inevitably influences the design of others and starts a chain reaction that gives people the wrong perception of architecture. While the growing awareness about global warming issues is thought to incite changes in human decisions and activities, architecture, on the other hand, continues to mislead. The aesthetics of a building remains more appealing than the elusive concept of a green building. This trend also uses, to wrong intent and purpose, the green label as a marketing tool. Designs promoting that label, cater to fame rather than society since most “green buildings” which boast good aesthetic features still use materials that carry a rich history of production and manufacturing. All for less goes against the very essence of the ‘green’ tags attached those buildings.

Ultimately, as architects, we are the sole definers of our own morality and ethics. We can be engaged or cynical in our approach to the very real problem affecting our planet. It is our civic responsibility to respond adequately in the face of the choice being presented to us.

In the face of the dramatic and pervasive consequences of global warming around the world and the flagrant role factored in by the construction industry in the process, one should re-evaluate our ethos as architects. We, as designers of a better future, should adhere to a moral obligation to constantly change and improve our design principles and philosophies. Our aim should be to not only address architecture towards the proper audience but also align it to the present and future ecology of our planet.

The sheer importance of striving towards sustainability cannot be emphasized enough. Our planet has suffered and wept and yet we continue to turn a deaf ear to its pleas. We willingly blind ourselves to the fact that day by day, our climate continues to be subject to upheavals, our carbon dioxide emission is sky rocketing, our glaciers are retreating and our sea levels are rising, Little daily changes that over time accumulate to hasten global warming. Our planet threatens to self-combust and we are watching passively. It is important to realize and acknowledge our responsibility in this process. As architects, we can be advocates for change. The essence for an ethically oriented architecture should encompass various factors, all with the same goal in mind: striving for an ecological future.

Architecture, unlike philosophy, cannot complain of a logical deficiency. Instead, it is ever dynamic and epitomizes poiesis, which is the making of things, either material or virtual. Whether it is at a conceptual level or firmly grounded in reality, architectural projects interfere with society and with our planet, thus contributing to the transformation of the world. Such transformation should be closely monitored and effectively channeled. Architects should be sensible and ethical in their endeavors and strive towards creating shelters that cohabit with nature. It is high time for us to become personal and professional advocates of a new kind of Architecture. Our work more than ever, should be clear in purpose, focused on the usage of appropriate materials, intent on pursuing not only urban construction but also regeneration of nature and “dedicated equally to the service of status and wealth as it is to social equity.” (Polyzoides 2007).

References:

- Berge, B. 2009. The ecology of Building Materials. Italy: Elsevier Ltd.

- Juhani, P. 1994. Six themes for the next millennium. The Architectural Review, CXCVI (1169): 74-79.

- National Aeronotics and Space Administration. n.d. Climate change: Effects. http://climate.nasa.gov/effects/ (accessed March 11, 2012).

- Salingaros, N.A, Masgen II, K. G. 2007. Restructuring 21st Century Architecture Through Human Intelligence. International Journal of Architectural Research 1(1): 36-52.

- Polyzoides, S. 2007. If I were a young architect. International Journal of Architectural Research 1(3): 183-188.

Related Posts :

Category: Article

Views: 4624 Likes: 0

Tags: Al Gore , Barack Obama , Climate , Climate change , Environment , Global warming , NASA