Info:

Title: RETHINKING RIO’S LANDSCAPE - Code: 7c42dContest: Rio de Janeiro / 2013

By: Bruno Amadei Machado

Views: 6466 Likes: 4

Votes:

Alejandro Zaera-Polo 11 Jeffrey Inaba 7 Jeroen Koolhaas 4 Hernan Diaz Alonso 1 Cristiano Toraldo di Francia 8 Pedro Rivera 56.0

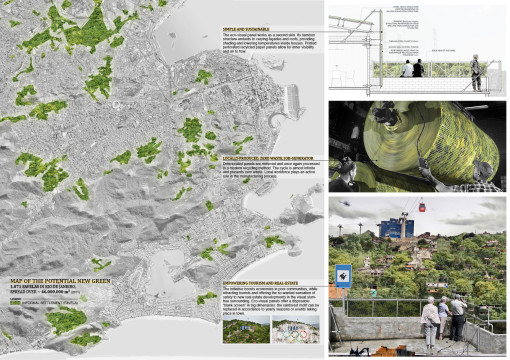

RETHINKING RIO’S LANDSCAPE

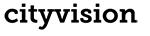

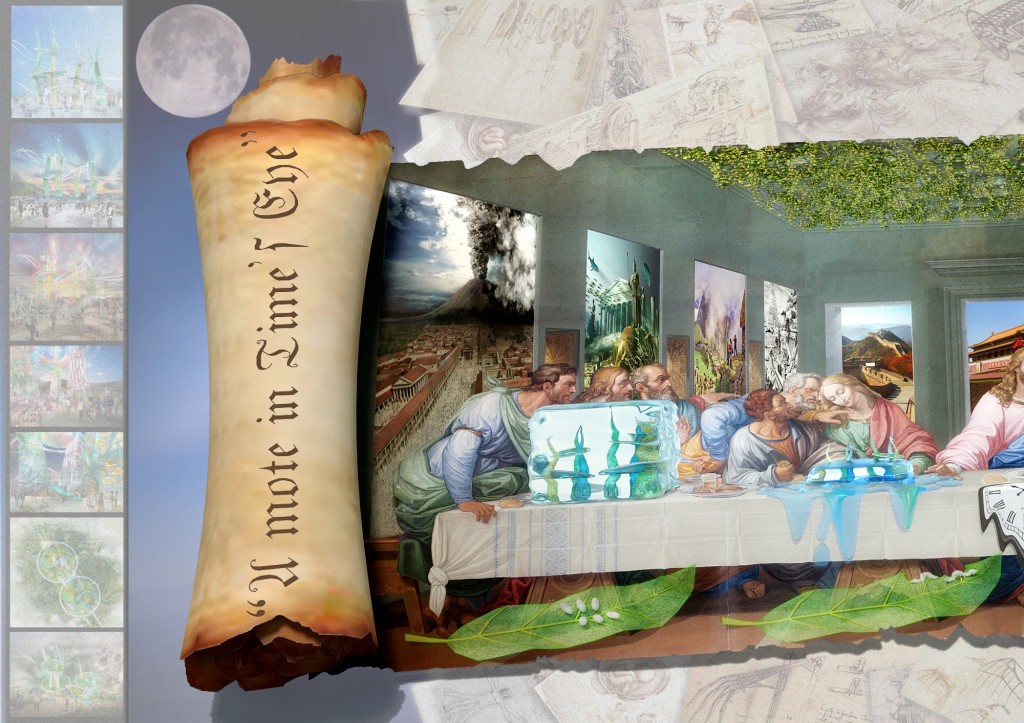

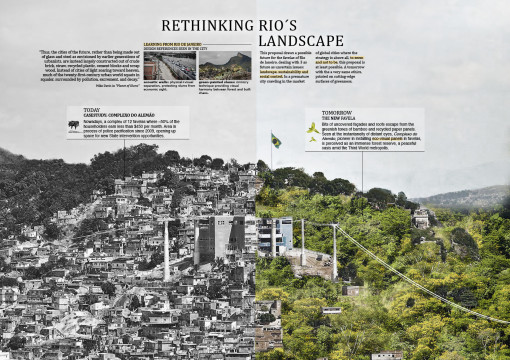

In 2011, Rio de Janeiro’s local government demanded Google to reduce the visibility of certain words on its Maps service, for allegedly touristic reasons. Two years later, names such as “morro” and “favela” (slum) almost disappeared from the city’s online maps. “Favela da Rocinha”, for ie., is now called only “Rocinha”. In 2009, kilometers of opaque acoustic barriers were raised along Rio’s main highway that connects the airport to inner town. Behind all the extension of these barriers, again there were slums: places lacking schools, sanitation and hospitals, but now apparently noise-free. In a research taken in 2011, 75% percent of the locals who were interviewed refused those barriers. But they are still there, both barriers and the poor. A few years ago, a project called “Cimento Social” (social cement) carried out, with the help of the Army, improvements in certain slums. In “São Carlos”, a centrally-located slum just below Rio’s biggest forest reserve, the improvement consisted solely in painting all façades green. All the houses in the neighbourhood, painted with one color: green. No differing tones, no exceptions. By taking in mind the above-mentioned references, this proposal draws a possible future for the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, dealing with three as future as uncertain issues: landscape, sustainability and social control. In a premature town crawling in the market of global cities where the strategy is, above all, to seem and not to be, this project is at least possible. We take as a case study “Complexo do Alemão”, nowadays a complex of 12 favelas where 50% of the householders earn less than $450 monthly. Since 2009, the area is under police control fighting against local drugdealers, inaugurating a peaceful moment for new State interventions. In the proposed “Complexo of Tomorrow”, bits of uncovered walls and roofs escape from greenish tones of bamboo and recycled paper panels. Seen at distant eyes, the pioneer favela in installing eco-visual panels is perceived as an immense jungle, a peaceful oasis amid the Third World metropolis. Eco-visual panels work as a second skin. Its bamboo structure embeds to façades and roofs, providing shading and lowering temperatures inside houses. Perforated paper panels printed with a vegetation motif allow for inner visibility and air to flow. Once deteriorated, panels are removed by local (unemployed) workforce and again processed in a modern recycling method, repeated infinitely with almost zero waste. The initiative boosts economies of poor communities, attracting tourists and offering the so-wanted safety sensation for new real estate developments in the visually slum-free surrounding. Eco-visual panels also work as a disposable blank screen in big dimensions: the rainforest motif can be redesigned in accordance to yearly seasons or events taking place in town. In sum, a hypothetical tomorrow presenting itself with a very same ethics, printed on cutting-edge surfaces of wonderful greenness.

Info:

Title: RETHINKING RIO’S LANDSCAPE

Time: 4 agosto 2013

Category: Rio de Janeiro

Views: 6466 Likes: 4

Tags: -